| Wild Geese Heritage Museum and Library

Home Page

Portumna, Co. Galway |

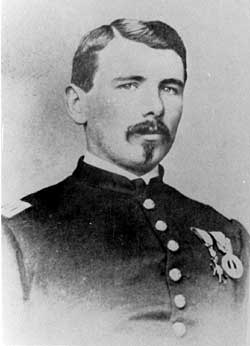

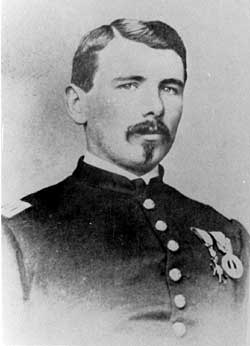

Captain (Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel) Myles Walter Keogh in U.S. Army

uniform, Civil War period. Courtesy of Imelda Keogh |

Myles Walter Keogh (1840-1876)

The Papal Medals and Sitting Bull

A strange title indeed - linking very famous people together in history. I came across this mystery a few years ago when I was researching the contribution of the Wild Geese to the development of European and American history. The story of Myles Keogh is featured on other sites, but it's only fitting that it should also be presented from Ireland. The mystery of the medal has been partially solved, and perhaps the reader will develop a fascination with all the events surrounding it. Here is how events unfolded.

The Early Years and the Papal War

Myles Walter Keogh was born on the 25th March 1840 at Orchard, Leighlinbridge, Co. Carlow to John and Margaret Keogh. His mother was previously Margaret Blanchfield of Clifden, Clara, Co Kilkenny. He was one of nine surviving children. When he finished school in Leighlinbridge, he attended St. Patricks College, Carlow.

In 1860 Garibaldi was organising the various states in Italy into one unified country, and was opposed by the Papal army of Pope Pius IX. The Pope appealed to Ireland and other countries for help in putting down this Revolution, and Ireland responded with 1,400 volunteers from all walks of life.

They arrived in Italy in the summer of 1860, and Myles was appointed a 2nd Lieutenant in the Irish Battalion of St. Patrick on the 7th August of that year.

He was stationed at Ancona, a port on the Adriatic, with the 4th Company, numbering 456 men. This city had a garrison of 5,700 Austrian, French, Swiss and Irish troops when it was surrounded by land and sea on the 12th Sept 1860, and on the 29th Sept the garrison surrendered, and Myles was made a prisoner of war.

|

Soon the Papal War ended, and most of the Irish Battalion returned home, with the exception of 46 men, including Myles, who remained in the Vatican as part of the Papal Guard. Every member of the Irish Battalion received a Papal Medal, Pro Petri Sede, for defending the Throne of Peter, with PIO IX PMA XV on it also.

Myles got a further honour for distinguished service and bravery, the decoration of The Order of Saint Gregory the Great.

Papal Medals courtesy of Imelda Kehoe |

The American Civil War

His mother died whilst he was in Rome, but he did not return home. Soon news of the American Civil War excited him and his friends. With Joseph OKeeffe, John Coppinger and Dan Kiely he arrived in New York on April 1st 1862. Three of them became Captains of Volunteers on the 9th of April 1862, and a week later Myles and Joseph O Keeffe were assigned as aides-de-Camp to Brigadier General James Shields, with Dan Kiely joining them when they reached the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. Stonewall Jackson and his Confederate Army overwhelmed the Federal Army here, but Myles and his troops distinguished themselves when they held a vital bridge at Fort Republic.

By the 1st of July, Myles and Joseph OKeeffe were transferred to the Staff of Brigadier-General John Buford, Commander of General Pope's Cavalry. Robert E. Lee and Jackson soon defeated the Federal Army at the 2nd Battle of Bull Run ( 30-8-1862 ) and Chantilly. He was transferred to the staff of General McClellan in September, and fought with him in the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam, the latter resulting in 25,000 casualties in a single day on 17th September 1862.

When Abraham Lincoln visited McClellan's army in October, Myles and five other officers were picked to escort him. Myles and Joseph O'Keeffe were transferred back to Brigadier-General Buford's staff a month later.

The following spring Lee defeated the Federal forces at Chancellorville, where Jackson was killed accidentally by his own men. Myles won commendation for a raid on Richmond, and this was followed by the greatest cavalry battle of the war at Brandy Ford.

The Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1st 1863, and lasted three days, with the Federals winning a great victory. Myles was breveted Major for gallant and meritorious services at the battle. The war ground on, with action at Brandy Station and Culpepper.

Buford became very ill, and Myles brought him to Washington, where he nursed him until he died on December 16th.

In January 1864, Myles was Aide to General Stoneman, and they joined General Sherman for the Georgia campaign. On April 7th he was promoted to Major. In July both he and General Stoneman were taken prisoners, but were exchanged two months later for Confederate officers.

He distinguished himself in several battles in the following months, but by the beginning of 1865 the south was reeling, and on April 9th 1865 Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House. The American Civil War was over and Myles had survived over 80 battles without injury.

He was still attached to General Stoneman's command in Tennessee, and in April 1866 he was brevetted Lieutenant-Colonel of Volunteers. During this post-war period, he became acquainted with the wealthy Throop-Martin family of Willowbrook, Auburn, New York, and especially with Cornelia or Nelly. They became friends and he was a constant visitor to Auburn from then on. The regular army was set up, and in May 1866 he became a Lieutenant in the 4th Regular Cavalry, and was transferred as Captain to the 7th Cavalry and posted to Fort Riley, Kansas in October 1866.

George Armstrong Custer (age 27) was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel in command. Myles was 26 and was 4th Senior Captain in the regiment. He commanded Troop I, and in November they were in Fort Wallace, a frontier post in Kansas.

The Indian Wars and The Battle of the Little Big Horn

Meanwhile back in Ireland, the family scene began to change. His brother Tom had married, and now lived at Park, Tinryland, Co. Carlow with his wife and three unmarried sisters, Ellen, Margaret and Fanny. His brother Patrick lived in Orchard, but there was a family lawsuit concerning same. His uncle, Patrick Blanchfield of Clifden, died on the 12th June 1867, leaving the property to his sister Mary, with no mention of Myles in the will. Seven years later in 1874, Mary left Clifden to Myles in her will.

During this time, there was a great deal of activity on the Indian front, and it was the subject of much debate all over the United States. Myles attended a wedding in Auburn in February 1868, but broke his ankle when he slipped on the ice and spent the next three months convalescing in Rhode Island and the Martin estate in Auburn.

He returned to Kansas in April and was promoted Inspector-General to the staff of General Alfred Sully. He missed Custers winter campaign of 1868, but joined him for a short while in September, before returning to his post as Inspector-General for the winter. Indian affairs were worsening, with the Sioux, Cheyennes and Arapahoes constantly on the warpath.

In June 1869 Myles was on sick leave, and he applied for his American passport at this time. It described him as 6 ft 1/4 inches tall, brown hair, blue eyes and florid complexion.

The following September he began his leave in Ireland, and spent a lot of time at Orchard, Park and Clifden.

In the spring of 1870 he retured to Kansas, where he was stationed at Fort Leavenworth. He scouted with Troop I under Custer until the 7th Cavalry went into winter quarters at Fort Hays in October.

The following three years, 1871-1873, Myles was stationed in Kentucky and South Carolina, where the army tried to enforce Government policy against fierce opposition from the Ku Klux Klan. His troop also hunted moonshiners. He moved to the Canadian border under Major Reno in summer 1873, to escort the Northern Pacific Boundary Survey as it prepared for the Railway. He missed Custer's skirmishes in the Yellowstone Area and his controversial expedition to the Black Hills in 1874.

Myles probably returned to Ireland in the summer of 1874, as his Aunt Mary had died leaving him Clifden in her will. It is accepted amongst his family in Ireland that he became engaged to Nelly Martin around this time, but no positive proof exists at the moment. Around this time also he experienced some health problems, but recovered.

He was back in America again in the summer of 1875. Indian affairs were deteriorating rapidly. All their treaties with the White Man were callously broken. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was scrapped when gold was found in the area. Their sacred ground was violated, and the buffalo was almost exterminated. General Sheridan ordered the 7th Cavalry into Dakota, their holy ground. They were forced onto reservations at short notice. General Terry was appointed to command an expedition, with Custer in command of the 7th Cavalry.

The most important chief among the Sioux nation and the Cheyennes was Sitting Bull, an Hunkpapa Chief and great medicine man. His main war Chiefs were Crazy Horse, Two Moon, Gall and Red Horse. Army Indian Scouts finally discovered an Indian village and a vast herd of ponies in the valley of the Little Big Horn.

Custer and his 7th Cavalry marched to the tune of Garryowen, with 12 companies and about 600 soldiers in total. Custer had orders to wait for reinforcements before attacking, but he ignored same. He divided his force into four. One company was to stay and guard the pack train and Gattling guns, whilst Major Reno and three companies were ordered to cross the river and attack from the south. Captain Benteen, with three other companies, scouted further south-west, whilst Custer himself with five companies moved downstream to reach the northern end of the village.

The Indian village contained 5,000 braves, fully equipped with repeating rifles, against Custers unreliable Springfield rifles. Major Reno was ambushed first and had to retreat with heavy casualties. Benteen joined him and they defended themselves for two days on high ground, but were unable to come to the aid of Custer.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn was fought on the 25th June 1876. Much has been written about it, with its own mysteries and legends. Crazy Horse, Gall and Red Horse closed in a pincer movement around Custer and his soldiers. Myles Keogh was second-in-command on the day, leading his own I Troop, Calhouns L Troop and F Troop under Captain Yates. Custer led his own Troop, his brother Tom's C Troop, and Captain Cookes E Troop.

There were no white survivors. The bodies were scattered over a wide area from near the Little Big Horn river up along the hill. Who died first or last? No one knows. All the soldiers except Custer and Keogh were scalped and mutilated.

Comanche

Picture the battle scene two days later when the remainder of the 7th cavalry came to witness. All around is stillness, and as far as the eye can see nothing moves. There are dead bodies everywhere, but in the distance there is a tiny movement. Moving closer a horse raises its head and neighs weakly. It is Comanche, the horse of Myles Keogh. He is taken to a nearby Army Post and nursed back to health, and eventually is transferred to Fort Riley, Kan. where he remained until his death in 1891. His body was then transferred to the University of Kansas, where it was preserved and mounted by a taxidermist. Today it is exhibited in a climate-controlled case on the fourth floor of the Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas. It is the Museums prime exhibit, representing as it does a symbol of the American frontier, and the equestrian role in taming the Old West.

Comanche was born in the wild in 1862 on the borders of Oklahoma and Texas. He became the mount of Myles Keogh in 1868, and they never parted, until the Little Big Horn.

The Legend of the Medal

It would be invidious of me to pretend that I have total and absolute knowledge of the events which took place on that eventful day at the LBH. I have read as many of the books, reports, articles as I could lay my hands on, before even beginning to write this section.

A noted Irish historian has stated in his book on the Wild Geese that Sitting Bull was wearing Myles Keogh's Pro Petri Sede medal around his neck when he was killed by his own Indian Police. He includes in his book a picture of the medal, by courtesy of the Irish National Museum. I have studied many reports from many texts, and I now include a synopsis of the best of them.

(a) The Indians said later that they found a medal attached by a chord around his neck, and it is suggested that this was the Papal medal.

(b) While many writers have stated that his body was not mutilitated because the Indians regarded the medal worn around his neck as a powerful charm, it may have been as a mark of respect for his courage. An Irish writer has claimed that when Sitting Bull died, Keogh's Pro Petri Sede medal was found on his body, the Sioux chief having taken it from around the neck of the dead Keogh and worn it since then as a tribute.

(c) When other cavalry units reached the LBH a few days after the massacre, Keogh's body was found unmutilitated, possibly because he was wearing a religious medal around his neck.

(d) Legend has it that the Native Americans would not touch Keogh's body because of the Papal medal which he wore.

(e) Keogh was only stripped, and wore a religious chain with a Papal medal around his neck, and this probably caused them to leave his corpse alone. It is notable that when Sitting Bull was killed in a later battle, he too was found to be wearing a Papal medal.

(f) In a book, The Last Years of Sitting Bull, I found the enclosed picture. The crucifix, as stated, was given him by Father de Smet. No mention is made of the medal.

(g) Captain Myles Keogh had not been disfigured. He lay naked except for his socks, with a Catholic medal around his neck, which is usually identified as an Agnus Dei, perhaps Agnus Dei is a familiar phrase. Romantics describe it as a cross hanging from a golden chain. Almost certainly this medal was kept in a small leather purse or sheath and Keogh most likely wore it suspended by a leather thong or length of chord. It was the Medaglia di Pro Petrie Sede.

Captain Edward Luce does not think that this medal was found on Keogh's body, but Lt. Godfrey - who was present - told artist E.S. Paxson in 1896 that it had not been removed. Trumpeter Martini, the last man to get out, insisted Benteen took the medal. Certain historians provide Keogh with two medals: one around his neck, another in his pocket. This is conceivable because the Pope awarded him, as a mark of special favour, the Cross of the Order of St. Gregory. Whatever the exact truth most scholars agree that he had the Pope's medal, and that it kept his corpse from being abused. But this sounds illogical, as most Cathlics in this army would not have been wearing religious emblems.

(h) This photograph with his Medaglia di Pro Petrie Sede was taken from the body of Keogh after he was killed, and afterwards recovered by Captain Henry J. Nowlan, 7th Cavalry.

(i) Myles wore a scapular or Agnes Dei on a chain around his neck. The Indians perhaps thought it was a magic amulet. I have read that Sitting Bull wore Myles Papal Medal around his neck after the battle. It may be true, because I have only seen the miniature medal, not the large one.

(J) The medal referred to in my book was the Pro Petri Sede, which was a very rare one, and was the one which was on the neck of Sitting Bull when he died. Some of his personal effects were recovered later in Canada, and returned to Ireland. In addition his Army uniform, spurs, sabre, sash and belt, an Army cap, plumed ceremonial helmet, epaulettes, letters and photographs and many other items were also returned. Some of these items were displayed for a short while in the National Museum of Ireland between the years 1954-1958.

Today a few items belonging to Myles are on exhibition in the Gene Autry Museum in LA. I can now state that the Pro Petri Sede and the Order of St Gregory the Great Papal Medals are back here in Ireland - but I have not seen them.

Details of his death will never be fully known, and we must depend on Indian testimony for some details. The Sioux say he was the bravest man they ever fought. He died fighting and encouraging his men to greater effort, with Comanche by his side. When the cavalry troops of the 7th arrived two days later, they found his body near his horse and surrounded by the dead bodies of his own troop. All the dead were buried on the battlefield, but on the 25th October 1877, Myles body was re-interred with full military honours, at Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn, New York. The dignified monument keeps watch over his restless spirit. May he rest in peace.

| References: | |

| Myles Walter Keogh, Imelda Kehoe

Captain Myles Walter Keogh, The Irish Sword Son of the Morning Star, Evan S.Connell Captain Myles W. Keogh, Jim Delaney Myles Keogh, Irish Echo The Irish at the Battle of the LBH, LBH Associates Newsletter Keogh, Comanche and Custer, Edward S. Luce The Wild Geese, M.N.Hennessy |

The LA Daily News

Bismarck Tribune 6-7-1876 National Museum of Ireland Research by John O'Hara, NY: Russel J. Daly, Washington DC Maryann O' Donnell, Jim Flavin and Bob Sabaroff, LA. Gary Tatum, Vacaville, CA Noel Spillane and Sean Egan, Dublin |

A special word of thanks to Imelda Kehoe in Kilkenny, for her friendship, advise, guidance and her deep knowledge of history. Also special thanks to Ann Harney, Norfolk, VA, who now manages the website following the death of our colleague Michael Barret.

We also mourn the death of our dear friend and fellow researcher, John Keane in Morristown, NJ. His wife, Terry, tells me that a strange thing happened as they walked into the church for John's funeral Mass - a formation of Wild Geese flew over the church. The music at the Mass included some of James Galway's airs - the first being The Lament for The Wild Geese.

Go ndeana Dia Trocaire ar a N-anam.

Copyright © Sean Ryan, 2002

Further Online Resources: | |

|

Comanche, Only Survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn

Comanche, Died c.1890, Lawrence, Kansas Myles Keogh Burial Place |

Myles Keogh, Born a Soldier

|