| Wild Geese Heritage Museum and Library

Portumna, Co. Galway |

Botany Bay 1791 - 1867

By a lonely harbour wall

She watched the last star falling

As the prison ship sailed out against the sky

But she'll live and hope and pray

For her love in Botany Bay

It's so lonely 'round the Fields of Athenry.

Introduction

The story of Botany Bay and the penal colonies of Australia and Tasmania is inextricably linked with that of the Great Famine. The emigrants and deportees came from deprived, impoverished, strife-riven rural areas, accustomed to violence, and where the Protestant ascendancy ruled with an iron fist. The famine emigrants were forced to leave the land they loved because of starvation and eviction. Those who were deported to Australia and Tasmania were already convicted of petty crimes, and those associated with rural strife and poverty. Leaders of rebellions and groups who were urging the people to resist exorbitant rents and tithes, were also deported. There are many reasons why I should write the story of Botany Bay.

Emigration and unemployment have been the scourge of Ireland for generations. The population of the Republic fell to 2.8m in 1961 - the lowest level since the Great Famine. But there has been a dramatic reversal. The total population in April 2004 was 4.04m - the highest figure since 1871, when it stood at 4.05m. The total number of immigrants arriving has fallen back to 50,100 in the last year, down from its peak of 66,900 in 2002. Emigration of 18,500 was the lowest since these figures began in 1987, and quite possibly the lowest since the Great Famine. Over half of them are in the 15-24 age group and most of them are heading for Australia/New Zealand. In other words, they are not emigrants at all but young people doing the modern equivalent of the Grand Tour.

My friend Tom Felle from Portumna worked as a journalist with the Irish Echo in Sydney until recently. Whilst there he visited the Clare Valley, which is 900 miles west of Sydney and north of Adelaide. Most of the settlers there though did not settle until the mid 1850’s, they came from Melbourne with the promise of new lands. The Clare Valley is one of the country’s top wine regions. The town of Clare is very beautiful, the main square is still called Ennis. Barry’s winery displays pages from my Wild Geese website on its walls. This family is related to the political Barry family of Cork City. Canberra hosted a Wild Geese conference a few years ago. John Wogan-Browne is an Australian email friend from an old Wild Geese family who provided some historical details.

I met the Roses of Tralee from South Australia and Darwin when they visited Portumna Castle in August 2004. They were both charming and chatty. Pamela Relihan came from Athelstone, South Australia, and Courtney Hare came from Casuarina, Darwin, Northern Territory.

It is a popular belief that Australian rules football was derived from Gaelic football. The case can be argued from the striking similarities between the two games in both general character and specific rules and from circumstantial evidence. The documented presence in Australia of that major Irish game, hurling, from the 1840’s suggests it is likely that the Irish brought their variety of football as well. Irish hurlers were said to have played the first game of football in Melbourne on October 12th, 1843. Earlier in that year, on St Patrick’s day, the first reference to football being played in South Australia spelt out the Gaelic origins of the players.

International Rules football is a hybrid sport developed in the 1980’s as a mixture of Australian rules football and Gaelic football. It was created in order to facilitate international matches between the representative teams of the Australian Football League and the Gaelic Athletic Association, which have been played annually since 1998 but date back in various forms to 1967.

A Brief History of Australia and Tasmania

Between 1616 and 1636, Dutch navigators explored Australia’s west, southwest, and northwest coasts. Explorers then began to believe they had found the mysterious southern continent. In 1642 and 1643, Abel Janszoon Tasman, a Dutch sea captain, sailed around the continent without sighting it. During his voyage, Tasman saw and briefly visited a land mass that he named Van Diemen’s Land. He thought this land was part of the continent. Actually, it was an island, which was renamed Tasmania in his honour in 1855.

All the early explorers reported unfavourably on what they had seen of Australia. The land was dry and barren, and the people had no gold or other riches. Then, in 1770, James Cook of the British navy became the first European to sight and explore Australia’s fertile east coast. Cook claimed the region for Great Britain and named it New South Wales.

Early Settlement. Before the Revolutionary War in America, Britain regularly shipped many convicts to its American colonies. This practice, which was known as transportation, helped relieve overcrowding in British jails. After the United States won its independence in 1783, Britain had to find a new place to transport convicts. In 1786, the British decided to start a prison colony in New South Wales. Captain Arthur Phillip, a retired naval officer, was appointed to establish the colony and serve as its governor.

In May 1787, Phillip sailed from England with about 570 male and 160 female convicts, about 200 British soldiers to serve as guards, about 30 wives of soldiers, and a few children. The group travelled in 11 ships and reached Botany Bay, on Australia’s east coast, on January 19th, 1788. On January 26th, Phillip established the colony’s first settlement on the shores of a large harbour about 7 miles (11 kilometres) north of Botany Bay. It was the first white settlement in Australia and the beginning of the city of Sydney. Tasmania, taz may nee ah, is the island state of the Australian Commonwealth. It is the smallest Australian state, and one of the most beautiful. Many Australians spend their vacations on the island.

History. In 1642, the Dutch navigator Abel Janszoon Tasman became the first European to reach Tasmania. He called the island Van Diemen’s Land, in honour of the governor of the Dutch East Indies (later Netherlands Indies). British convicts settled on the island in 1803. Great Britain granted responsible government to the island in 1855, and its name was changed to Tasmania. In 1901, it became part of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle was the seat of Government of Ireland from 1204 to 1921. This famous castle has its own beautiful website. I will concentrate on its Irish-Australian record office.

The Irish-Australian papers are extraordinarily rich in historical interest and in human content: So much so that even the experienced archivist cannot fail to describe them except as precious. Some indication of the documentary records in Dublin Castle can be conveyed by stating that the papers contain information not yet fully assessed, but estimated to cover some 25,000 named Irish men and women transported from all the 32 counties of Ireland to Australia: The greater proportion of the 30,000 men and 9,00 women estimated by one historian to have left Ireland compulsorily under the designation of convicts in the 63 years from 1791. There are files from 1791, in an organised and unbroken series up to 1836 which, though often containing no more than single pages, may in some cases consist of a large number of individual documents, up to a maximum of forty. Facsimile documents in the State Paper Office entitled ÒTransportation Ireland - Australia 1798-1848Ó, give greater detail of the people who were involved.

The records of the Chief Secretary’s Office consist of 347 volumes and 3,800 cartons of paper, each containing more than 200 documents. Among them are rich references to Australia and to the Irish who went there as convicts, free settlers or as enterprising emigrants. The records of one department of the Chief Secretary’s Office, the Convict Department, are of primary importance for research in Irish-Australian historical connections.

Year by year, under the title of the county jail in which the convicted person was held, the names and surnames are given separately for men and women, with details in each case of age, crime committed, sentence, when and before whom the trial took place and, in a final column, remarks such as the date and name of the hulk in which the convicted person was confined prior to embarkation and, sometimes, the name of the transportation vessel. However the address, parish or town of the convicted person is absent.

National Archives of Australia

In terms of modern written history, Australia is still a young country. It only began to collect its documents after World War 1. The collection was housed in various areas, but now it is centralised in a beautiful new building in Canberra. The migrant selection documents and naturalisation papers of millions of people who have come to live in this country, are also of major interest for historians and genealogists. The copyright collection dates back to colonial times, a rich source of Australian creative endeavour and social history.

Each capital city in Australia has its own archives and records department, all with their own websites which may be accessed in the usual manner. For the sake of brevity I will concentrate on the state records of New South Wales, which are located in Sydney. The main building is situated at Kingswood. The Sydney Record Centre Reading Room is located in the historic Rocks area at 2 Globe Street. The Western Sydney Record Centre Reading Room is located at 143 O’Connell St, Kingswood. The database on Irish Convicts to New South Wales 1791-1827 contains details of Irish Convicts who were transported to New South Wales during that period. It contains lists of Irish state prisoners who were tried in Ireland, and convicts who were tried outside Ireland whose native place was in Ireland. There is a fine list of database primary sources including National Archives of Ireland, Ireland-Australia Transportation Records Database 1791-1868. The National Archives of Ireland holds a wide range of records relating to transportation of convicts from Ireland to Australia covering the period 1788 to 1868. In some cases these include records of members of convict families transported as free settlers.

To mark the Australian Bicentenary in 1988, the Taoiseach presented microfilms of the most important of these records to the Government and people of Australia as a gift from the Government and people of Ireland. A computerised index to the records was prepared with the help of IBM, and is located for use at various locations in Australia.

The next topic is The Irish Rebels to Australia 1797-1806. This database contains details of Irish convicts who were transported to New South Wales in the period 1791-1827, including a list of the ships that the rebels came in. The exact number of rebels sent cannot be ascertained due to the poor state of information on the shipping indents. Only the Minerva identifies all her rebels on board. The highest figure can be put at nearly 800, while the lowest is conservatively placed around 325. A full list of database primary sources is also included.

Ireland and Australia have produced a mountain of archives readily available to all of us, but a lot more work needs to be done. No archives exist at all in Ireland about the Wild Geese, but they are scattered throughout Europe. Clearly something should be done similar to Australia.

Botany Bay - Its Place in History

I am always curious as to how places acquired their names. It is said that New York is named after the Duke of York, later to become James 11, King of England. The Irish for Portumna is Port Omna, which means the Port of the Oaks. The Irish for Donaskeigh is Dun na Sciath, which means the Fort of the Shields. The Irish for Kilcormac is Cill Chormaic which means the Church of St Cormac. Cill can mean either a wood or a church, and there are hundreds of place names beginning with this word in Ireland.

Botany Bay, Ireland and the penal colonies are forever linked together in myth, legend and song. The aboriginal people were the earliest inhabitants of the Botany Bay area. They set up camps along the banks of the Cooks River and on the shores of Botany Bay, hunting, fishing and gathering food. Trees and plants provided the raw material for food, medicine, implements and weapons. It was discovered by Captain James Cook on April 29th, 1770 - the first European to land on the east coast of Australia. He named it Stingray Harbour. Two of his companions, Daniel Solander and Joseph Banks, were botanists, and they were entranced by the number of flowers blooming in the area. Banks persuaded Cook to change its name to Botany Bay. Their vivid impressions were responsible for the projected location there of the convict establishment under Captain Arthur Phillip of the Royal Navy in 1788.

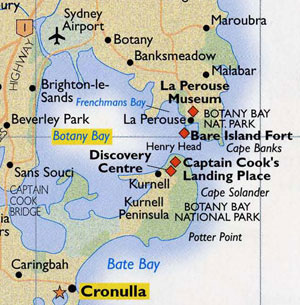

Botany Bay is just south of Sydney Harbour and acts as Sydney’s industrial port. Botany Bay was found unsuitable for settlement in 1788 so the First Fleet rowed north to Port Jackson (aka Sydney Harbour) and settled on a fresh water stream, which they named Sydney Cove. Governor Phillip called the site Sydney Cove in honour of Lord Sydney, the Secretary of State for the colonies. So began Sydney (Cove dropping from the name) with 568 male and 191 female convicts and 13 children; 206 marines with 26 wives and 13 children; and 20 officials. It now has a population of well over 4 million. From about 1800 onward, when the first Irish political prisoners landed, they were kept in either Paramatta, in West Sydney, or Botany Bay.

Botany Bay is now a modern municipal city, with a population of 300,000. Its population would have been only about 3,000 in the early 1800’s, mostly political prisoners and a few platoons of Redcoats. Sydney Airport’s third runway juts onto the bay. A monument on the south shore marks the site of Cook’s landing.

The Organisation of the Transportation System in Ireland

The Cromwellian period confiscated Irish Catholic estates and gave them to Protestant settlers. By 1778 only 5% of the land remained in Catholic ownership, though at the beginning of the previous century they had held 90%. Managing their plots, the greater part of the population lived in constant dread of rent-day or eviction. When landlords attempted to increase rents, to evict unsatisfactory tenants or to enclose more land for cattle grazing, they met with fierce opposition from the desperate tenants who formed secret societies to protect themselves. The Ribbonmen, the Whiteboys and the Defenders were among the most active of these societies. It was a violent society in which justice was administered swiftly.

Crimes associated with disputes over land were classed as agrarian, whilst rebels and political offenders were in a different category. Starvation and the need to keep body and soul together resulted in much stealing of cattle and sheep. Most of the crimes were trivial offences such as the stealing of a chicken or a scarf. Some were rounded up during local disturbances or arrested for vagrancy. Others committed petty offences so that they would be transported, because they could not stand the hunger, the hopelessness and the humiliation. What did we do to them, that they would torture us so?

Perhaps a few lines from that great negro spiritual, Old Man River, may help explain the penal system in Ireland at the time.

Don’t look up and don’t look down

You don’t thus make the bossman frown

Bend your

knees and bow your head

And dig them

spuds until your dead

Arrest and confinement in the local county or city jail followed, until the case was brought forward at one of three venues. Where the court imposed a sentence of transportation, it was usually for seven years, less often for fourteen years or for life. After sentence the convicted person was held in the local county jail, the convicts were then transferred from the county prison under heavy escort to Cobh, Co Cork or Dun Laoghaire, Co Dublin. They were then imprisoned in local jails or converted vessels, known as hulks, until the transportation ship was ready.

About one third of those sentenced to transportation submitted or had petitions submitted on their behalf. They often state the background circumstances to the alleged crime as seen by the individual concerned. They describe the plight of aged parents who fear the loss of the support of their industrious sons and daughters, or of distressed wives with large families of young and helpless children reduced to a level of hopelessness and poverty verging on starvation. The petitions were considered by the trial judges, officers of the Chief Secretary’s Office, with the Lord Lieutenant having the final say. Sometimes the death by hanging penalty was reduced to transportation for life.

The movement of prisoners from jail to jail, from jail to hulk and from hulk to the ship was very hazardous. Prisoners attempted to escape, mobs gathered along the road and at the quayside. Relatives made desperate attempts to see their loved ones before they sailed for Botany Bay.

The ship was prepared for the voyage, by putting on board the necessary food, water and other provisions, the shaving of the male convicts, the outfitting of all for the voyage and the checking of conditions on board before departure. When all was ready the ship set sail for Australia.

The Voyages

The male and female prisons in the sailing ships were located below deck. They were poorly ventilated, had poor sanitation and were generally filthy. Each had a hospital and a doctor. The following chart illustrates the movement of the ships from 1791 to 1867.

These are the codes for the chart.

1 = The year of departure, 2 = The number of ships, 3 = The number of prisoners,

4 = Journey time in days,

5 = From/to, C = Cobh, S = Sydney, D = Dun Laoghaire

V = Van Diemens Land, WA = Western Australia, E = England

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1791 |

1 |

159 |

155 |

c/s |

|

1793/96 |

4 |

705 |

172 |

c/s |

|

1797 |

1 |

188 |

141 |

c/s |

|

1799/1805 |

9 |

1239 |

198 |

c/s |

|

1809 |

2 |

199 |

156 |

c/s |

|

1811-12 |

2 |

380 |

171 |

c/s |

|

1813 |

2 |

313 |

177 |

c/s |

|

1814 |

3 |

440 |

246 |

c/s |

|

1815 |

2 |

309 |

155 |

c/s |

|

1816 |

1 |

144 |

159 |

c/s |

|

1817 |

3 |

592 |

138 |

c/s |

|

1818 |

5 |

764 |

128 |

c/s & c/v |

|

1819 |

7 |

1028 |

119 |

c/s & c/v |

|

1820 |

5 |

734 |

132 |

c/s |

|

1821 |

2 |

341 |

127 |

|

|

1822 |

3 |

361 |

121 |

c/s |

|

1823/1824 |

8 |

1153 |

135 |

c/s |

|

1825/1826 |

12 |

2011 |

123 |

c/s |

|

1827 |

8 |

1449 |

121 |

c/s |

|

1828 |

6 |

1084 |

139 |

c/s |

|

1829 |

6 |

1128 |

117 |

c/s |

|

1830 |

6 |

1078 |

121 |

c/s |

|

1831 |

8 |

1370 |

132 |

c/s |

|

1832/36 |

38 |

5300 |

117 |

c/s |

|

1835 |

2 |

431 |

Lost at sea |

|

|

1837/39 |

20 |

3000 |

118 |

c/s |

|

1845/47 |

12 |

1800 |

107 |

c/v |

|

1848/49 |

9 |

2153 |

105 |

c/v |

|

1850 |

2 |

587 |

101 |

c/v |

|

1851 |

3 |

896 |

103 |

c/v |

|

1851/1853 |

8 |

2066 |

105 |

c/v/d/v |

|

1853 |

1 |

285 |

89 |

c/wa |

|

1867 |

1 |

62 |

89 |

c/wa |

|

_______ |

||||

|

Grand |

Totals |

202 |

33,749 |

The above chart has been compiled from a book named Botany Bay by Con Costello. He states that 39,000 were sent directly from Ireland comprising 30,000 men and 9,000 women, in 212 ships between 1791 and 1853. He also states that 162,000 including 25,000 women were transported from Ireland and Britain in the years between 1787 and 1868. About 6,000 Irish were apprehended and transported from England. In his essay in the book entitled Australia & Ireland Bicentenary Essays 1788-1988 , Mr Costello states that 37,432 Irish prisoners were transported in 212 ships to Australia, from 1791 to 1868. Of this total 8,419 women and 28,022 men disembarked, the remaining 991 having either died or escaped on the way.

In his book The Convict Ships, Charles Bateson states that during the span of eighty years, 158,702 male and female prisoners were landed in Australia from England and Ireland. In addition 1,321 prisoners came from other countries making a grand total of 160,023. In his appendix the author states that 162,119 prisoners probably sailed from England and Ireland between 1788 and 1868. He notes that this figure is 2,246 fewer than the figures of A.G.L Shaw’s book Convicts and the Colonies. This indicates the difficulty of interpreting the conflicting official figures, apart altogether from human error.

A paper by Rena Lohan, Archivist, National Archives Journal of the Irish Society for Archives, Spring 1996, states that between 1787 and the termination of the system in 1853, Australia received over 160,000 convicts, approximately 26,500 of whom sailed from Ireland. Clearly there is a need for someone to produce a ship by ship master chart of the voyages between Ireland and Australia during these years. Perhaps a student of history would undertake this project.

The prisoners were each issued with two sets of clothing and footwear for the long 13,000 mile journey to Australia. Many of them suffered from a variety of diseases as a result of their confinement in jails and hulks, but the medical examination prior to embarkation was haphazard and indeed for many years was a useless formality. The provisions were generally of good quality, but the prisoners received less than their due because the rations were not always truly served. The ships stopped at various ports en route to take on provisions and for repairs. The actual transportation of prisoners was entrusted to private contractors, who furnished vessels, crews, provisions, clothing and even in some instances, the prisoners’ guards. Nearly all the evils associated with the conveyance of prisoners had their origins in the contract system. It was responsible for incalculable human misery, suffering and loss of life. The contractors derived no financial benefit from delivering the prisoners in a sound and healthy state. Dead prisoners were more profitable than the living. Dead prisoners do not eat, and tell no tales.

Informers always alerted the crews to mutinies and disturbances. At least a dozen were executed, whilst many more were flogged with the cat-o-nine-tails. Most men survived this form of torture, but some of those who received over 800 lashes died within a few days. Historians have noted that when the prisoners were treated humanely and with kindness, they arrived healthy and in good spirits. The opposite was true where the ship’s master was a sadist and a brute.

The Risings of 1798, 1803, 1848, 1867

During the period under consideration the majority of the crimes committed in rural Ireland were due to poverty or to disputes over land. The offenders were mostly from the labouring classes, and often illiterate and ignorant. This was not a reflection on themselves but on the regime that kept them ignorant. Irish history is filled with stories about Mass rocks and hedge schools. The political movements which led to the formation of the United Irishmen and the Young Irelanders and the consequent Risings of 1798, 1803, 1848, produced another type of offender, often well educated, articulate, and landed.

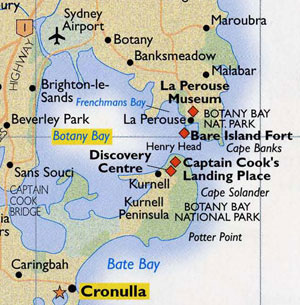

Towards the close of 1791,

Theobald Wolfe Tone, a young Protestant barrister of great ability, who had

devoted himself to the service of the Catholics in their efforts for

emancipation, visited Belfast, and met some of the popular leaders. They founded

the Society of United Irishmen with two principal aims - parliamentary reform

and Catholic Emancipation. The British government became alarmed at the

prospects of an independent United Ireland with French backing. They resolved

to provoke and goad the people into insurrection.

Towards the close of 1791,

Theobald Wolfe Tone, a young Protestant barrister of great ability, who had

devoted himself to the service of the Catholics in their efforts for

emancipation, visited Belfast, and met some of the popular leaders. They founded

the Society of United Irishmen with two principal aims - parliamentary reform

and Catholic Emancipation. The British government became alarmed at the

prospects of an independent United Ireland with French backing. They resolved

to provoke and goad the people into insurrection.

An army of spies and informers was recruited, and they kept the junta in Dublin Castle briefed on all developments. The aggressively Protestant Orange Societies, which sprang up about 1795, were composed almost exclusively of churchmen, and professed a strong loyalty to the crown and constitution. They supplied many recruits to the Yeomanry corps raised at this time for the maintenance of order.

Early in 1796 the Irish Parliament passed an Insurrection Act of a severity which would have been impossible in Britain. It compelled arms to be produced, imposed the death penalty for administering an unlawful oath, and transportation for life for taking such an oath. The excesses of the ill-disciplined troops and militia, who exceeded even their brutal orders, were bitterly denounced by Grattan’s minority in Parliament and even in the English House of Commons. The Government now went on to provide a further armed force, that of Yeomanry, which consisted of Protestant tenants and townsmen commanded by gentry under commission from the Crown. These were actively used and imparted to the later operations the savage spirit of religious partisans. At the outbreak of the rebellion the Government could count upon not less than 15,000 regulars, 18,000 militia, and 50,000 Yeomen, badly disciplined and shockingly out of control. But it is to be noted that of the two latter forces the Yeomanry were Irishmen, and many of the militia were Catholics. The United Irishmen had a force of 150,000 with able and educated leaders. Floggings, burnings, tortures, the shooting and hanging of men, were now a fate that even the most innocent might fear from hordes of soldiers roaming the countryside out of control. Lurid pictures of the atrocities, which led to the Insurrection and accompanied its suppression, were published in The Irish Magazine (1808-10). Hepenstall, a gigantic soldier in the Wicklow Militia, lives in the epitaph – “Here lie the bones of Hepenstall, judge, jury, gallows, rope and all.” They had portable triangles and gallows on which men were flogged and hanged, on the word of an informer.

A general insurrection was planned for May 23rd, but the government struck at once, and arrested the leaders, so the rebellion was deprived at one blow of its organisers. Lord Edward Fitzgerald died of wounds inflicted on him when he was arrested. Wolfe Tone was in France. But a rising broke out on May 24th. In Wexford, Catholic Churches and houses were burned. Perhaps a few lines from Boolavogue may help us to understand how it all started in Wexford.

A rebel hand set the heather blazing, and brought the neighbours from far and near. Then Father Murphy from Old Kilcormac spurred up the rocks with a warning cry, “Arm, arm”, he cried, “for I’ve come to lead you for Ireland’s freedom we fight or die.”

After some initial success the rebels, deprived of leadership, were defeated and made their way home. Father Michael Murphy was killed during the attack on Arklow. Fr John Murphy was captured and executed without pity. Wolfe Tone committed suicide in prison. Over 800 rebels were transported to Australia during this period. The Catholic Priests were tortured and threatened with execution in order to force them to reveal the secrets and names of the rebels.

Memorial Statue in Youghal |

|

|

Fr. Peter O’Neill, the Parish Priest of Ballymacoda, Co Cork was aged 50 when transported in 1800. He had been accused of involvement in the death of an informer. General Loftus ordered him to be flogged with a cat which had scraps of tin knotted into it. In the handball alley at Youghal, the Priest was stripped and put on a triangle. Six soldiers, two at a time, left and right handed men, flogged him until he had been given 275 lashes. Showing him the bloody bodies hanging on the gallows, the officials threatened that they would hang him, and cut off his head, and throw his body in the river, if he did not reveal the names of the United Irishmen which he knew from the confessional. As they failed to extract any information from him, he was transported to Australia. In November 1802 permission came from Ireland for Fr O’Neill to return home, and the Governor expressed sorrow at his departure. He returned to Ballymacoda and remained there until he died at the age of 86 in 1835. The local GAA Park is named Fr O’Neill Park.

Fr. James Dixon was a Curate in Crossabeg Parish in Co Wexford when he was arrested, having been accused of administering the United Irishmen’s oath, of singing rebel songs, and wearing a medal inscribed “Erin Go Bragh”. He was sentenced to death, but this was commuted to transportation for life, and he left Cobh on August 24th, 1799.

After a few years in the colony Fr Dixon was permitted to say Mass publicly. At the first public Mass on the May 15th, 1803, Fr Dixon wore as a vestment an old damask curtain. There was no altar stone, and the chalice had been made from tin by a convict. The regular Masses had a most salutary effect on the Irish Catholics.

|  |

In 1809 Fr/ Dixon was granted permission to return to Ireland to see his parents, where he was joyously received by his parishioners, who built a presbytery for him beside the church at Crossabeg. Fr Dixon died as Parish Priest of Crossabeg in 1840 aged 82. His grave, close to his church, became a place of pilgrimage, and pious people came to pray and take away earth from his grave. His remains were reinterred in 1913 and a fine memorial was erected over the grave. There have been many visitors to the grave, notably representatives of the Catholics in Australia, including Archbishop Kelly, Archbishop Mannix, Archbishop Carroll and many others.

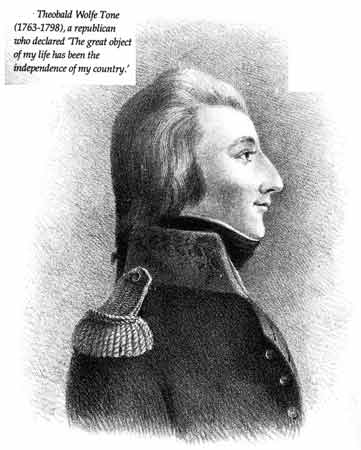

In 1802, Robert Emmet, a

gifted, earnest, noble minded young man of 24 years, attempted to unite the

United Irishmen. His plan was to attack Dublin Castle and Pigeon House Fort and

he had intended to rise in 1803. July 23rd was now fixed, on which day he

expected a contingent from the celebrated Wicklow rebel, Michael Dwyer. By some

misunderstanding the Wicklow man did not arrive and the insurrection was

hopeless. He might have escaped but he insisted on remaining to take leave of

Sarah Curran to whom he was secretly engaged. On September 20th, 1803, he was

hanged in Thomas Street. His final words from the dock are memorable “When my

country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and only then let

my epitaph to written.”

In 1802, Robert Emmet, a

gifted, earnest, noble minded young man of 24 years, attempted to unite the

United Irishmen. His plan was to attack Dublin Castle and Pigeon House Fort and

he had intended to rise in 1803. July 23rd was now fixed, on which day he

expected a contingent from the celebrated Wicklow rebel, Michael Dwyer. By some

misunderstanding the Wicklow man did not arrive and the insurrection was

hopeless. He might have escaped but he insisted on remaining to take leave of

Sarah Curran to whom he was secretly engaged. On September 20th, 1803, he was

hanged in Thomas Street. His final words from the dock are memorable “When my

country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and only then let

my epitaph to written.”

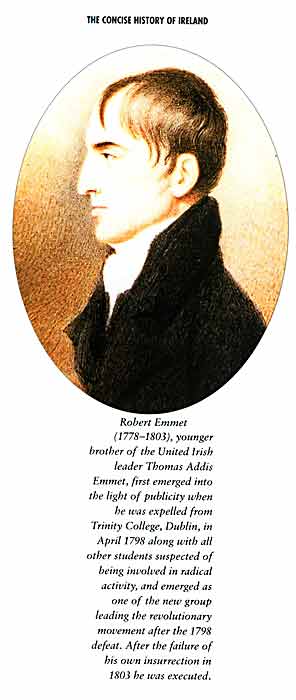

I have written extensively about the Young Irelanders in my story about the Great Famine. The most remembered of the leaders is the Ulster Presbyterian solicitor John Mitchell. His newspaper,The United Irishman, advocated passive resistance by the small farmers with resort to violence as a final measure. He escaped to America and he returned home in 1874. Elected as MP for Tipperary, he died at his old home at Newry in March 1875. During his time in America, Mitchell published his Jail Journal, regarded as a classic in prison literature.

The Fenian uprising was doomed to failure, and 62 of the leaders were transported to Australia. Some of them escaped to America. However, it had not been the ambition of all the prisoners to escape from the colony. In 1869 when 45 of them were pardoned, 7 elected to remain behind, while the remainder returned to Ireland or went to America.

It was considered unlucky to be involved in the torture or execution of Catholic priests. There is a strong tradition that many who took part in Fr O’Neill’s degradation suffered tragedies later on. One of these beliefs was that a man, who grinned in amusement at Fr. O’Neills suffering during the flogging, was semi-paralysed soon afterwards, and his face was permanently twisted - such that it appeared it was frozen in a grin. In my native parish in Tipperary, the local landlord, Sir Thomas Maude, was primarily responsible for the execution of Fr Nicolas Sheehy in Clomel in 1766. When he died his body had swelled up to an enormous size and there was a horrible stench from his room. Fr Tablot from Portroe, Nenagh, was tied to a tree in the landlord’s demesne, and then flogged. He died due to ill-treatment. Soon after this incident the landlord fell from his horse and was killed.

The Manchester Martyrs

The Irish Repubblican Brotherhood (IRA), which formed the core of the Fenian movement, was founded in 1858, but it was some years before it showed much activity. The movement was strongest among the Irish exiles in the United States, South Africa, Australia and Great Britain. In Ireland it was consistently opposed by the Roman Catholic Church. The organisation was originally based on circles divided into sections of officers and men. The Centre (Colonel) was known as A; nine sub-centres known as B or Captains; nine C’s or Sergeants and for every C nine D’s or Privates. At this time the population of England included almost one million Irish with a large proportion of them in and around Manchester.

Thomas Kelly was a farmer’s son from Mountbellew, Co Galway, who worked in Loughrea before emigrating to America. Timothy Deasy was a Corkman who also emigrated to America. They both became involved with Fenian activities in its earliest days in 1858. Kelly became Colonel and Deasy became Captain. They both fought with distinction in the American Civil War. They returned to Ireland and set up the Fenian headquarters in London in January 1867. The uprising was scheduled for March 5th and they planned to seize a large arms and ammunition store at Chester Castle, then rush the contents to Ireland. The plot was betrayed by an informer. Kelly and Deasy were arrested in Manchester in September and were lodged in jail.

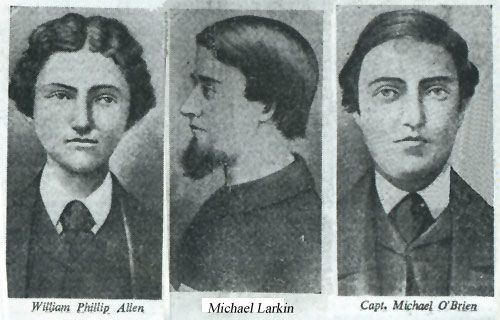

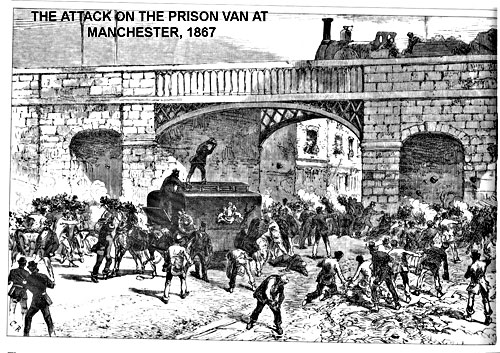

A rescue plan was put into operation. On September 18th, as the prison van was travelling along Hyde Road, from the court to the jail, it was attacked by 30 Fenians. A shot was fired at the lock of the van, but the bullet accidentally killed Sergeant Charles Brett. Kelly and Deasy escaped and were never recaptured. A general roundup of Fenians ensued, but only five were charged with murder. The trial of Allen, Larkin, O’Brien, Maguire and Condon opened on October 28th before Mr Justice Blackburne and Mr Justice Mellor, and lasted for five days. The jury found them guilty of all charges. Maguire was set free because of false evidence, and Condon was released because he was an American citizen. Thousands of petitions pleading clemency were submitted, but all to no avail. The Manchester Martyrs were hanged at Salford Prison, Manchester, November 23rd, 1867. William Philip Allen, aged 19, was a native of Tipperary town. Michael Larkin, aged 30, was a native of Lusmagh, Co Offaly. Michael O’Brien, aged 30, was a native of Ballymacoda, Co Cork. Amazement, shock and horror was the reaction of the world press. Ireland had never been short of martyrs, but there was a poignancy about the history of Allen, Larkin and O’Brien, which made their execution the signal for an explosion of anger and revulsion against British rule in Ireland. Demonstrations, funeral processions and public meetings were held in most towns in Ireland and England. In New Zealand on March 8th, 1868, 5 persons were fined £20 each for having taken part in a procession in honour of the Manchester Martyrs, and the Rev Fr Larkin and Mr Manning, Editor of The New Zealand Tablet, were each condemned to a month’s imprisonment.

Gladstone became Prime Minister of England in 1868, and he began by turning his attention to the question of disestablishing the Church of Ireland. The need to address the issue had been made patently clear by the publication of the results of the 1861 census, which showed that out of a population of 5.75 million, 4.5 million were Catholics, and 700,000 were Protestants. The Irish Church Act 1869 broke the official connection between church and state in Ireland. A series of Land Acts secured a fairer relationship between landlords and tenants. Thus was marked the beginning of the end of the Protestant ascendancy and landlordism in Ireland.

Free Emigrants and Emancipists

It is impossible to write about the history of the Wild Geese and the emigrants from Ireland without delving into the histories of the countries that they gravitated towards. Thus the histories of the countries of Western Europe, America and Australia are indelibly linked with the history of Ireland. Almost 10 million people emigrated from Ireland between the years 1690 and 1960. But there was one essential difference between all the other countries and Australia. In all these countries the Catholic Irish entered a firmly stratified society, an already elaborated class structure, and an established economy. But in Australia everything had to start from scratch. Only a few colonial officials and the native aborigines existed. Thus the Irish carved out for themselves a large slice of Australian history.

In round figures, 300,000 free emigrants and 45,000 prisoners sailed to Australia at the end of the 18th century and during the 19th century. There were considerable variations in the relative density of Irish settlement from place to place. Two colonies were always below the average for the continent. In South Australia, the Irish constituted only 17-18% of the total population. In Tasmania the proportion was only 15%. In New South Wales, the Irish settled much more heavily south than north of Sydney. The Irish were numerous in the Clare region of South Australia. The general pattern which emerges is a minimum Irish proportion of 15% and a maximum Irish proportion of 35% in almost every place and region in Australia. The Irish, especially the Catholic Irish, were rarely to be found in the higher financial employments.

On the other hand, in the professions of law, politics and journalism, the Irish were probably over represented. The Irish were grossly over represented in some colonial police forces, but only a small proportion in the public services. Generally, the lower the occupation in the social scale, the higher the proportion of Irish Catholics. In 1933, Catholics constituted 19% of the total Australian population. The following are the proportions in the various income categories: Class 1, the highest income group, 15%, Class 2, 17%, in Class 3,4 & 5, 18% and in Class 6, the lowest income group, 20%. Catholics represented 85% of Irish emigrants as against 75% at home. The current population of Australia is 20.4 million, of which 3.5million have an affinity with Ireland.

The Governors usually inspected the prison ships on arrival, and after checking the prisoners they demanded the documentation, but invariably there was none. The Indent lists, giving details of the transportees, often did not reach Sydney until many years after the arrival of the prisoners. This placed the officials in a very awkward position, and the prisoners were able to convince them of the brevity of their sentences. When the prisoners had sufficiently recovered from their ordeals at sea, they were allocated their work stations. Many of them possessed a wide range of professions and trades, including army officers, doctors, teachers, attorneys, blacksmiths, silversmiths, carpenters, plasterers, butchers, weavers and many more. The unskilled men were put to work at building the roads and bridges, or developing the land. When their sentences expired they were granted tickets-of-leave, and so were free men. The great majority of these free people remained in Australia. Anticipating emancipation, many of them encouraged their wives and families to join them in a new life in a land of opportunity. Several free transport schemes were designed to enable Irish people to emigrate to Australia.

But all was not so rosy in the garden. Some of the newly arrived men could not adapt to the rigorous life of the colony, and they made repeated attempts to escape. There were many insurrections, such as the Castle Hill insurrections in March 1804. When they were captured they were shipped to Norfolk Island, 1000 miles east of Sydney. It was said to be next door to hell, and that it was better to burn men alive rather than send them to Norfolk Island. Those that were hanged were glad of the relief to oblivion. It is impossible to comprehend how men who had suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, could end up with a rope around their necks, on a remote Island, far from their native shore. The answer my friends is blowing in the wind, the answer is blowing in the wind.

The Catholic Church in Australia

The Protestant Ascendancy thought that the correct place for the Irish was at the bottom of the ladder, and that they should be glad to be ruled by superior, intelligent people such as themselves. But the Irish were aware that Australia was a new and free country, and that they had every right to shape its destiny. But they lacked leadership. Back home this leadership was provided by the Catholic priests.

Aboard the ships which left Ireland in August 1799 were Fr James Harold, Fr James Dixon and Fr Peter O’Neill. After a few years in the colony Fr Dixon was permitted to say Mass publicly. A Government proclamation of April 19th, 1803, announced this fact, and ordered that during the service, which was to be at 9 am on Sunday morning, there was to be a Òno seditiousÓ conversation which might cause disturbance, nor were Protestants to behave in an anti-Catholic fashion. The regular masses had a most salutary effect on the Irish Catholics . Fr O’Neill returned home in November 1802, and Fr Dixon returned in 1809.

Following the departure of Fr Dixon from Sydney there was a lapse of 8 years before another priest came there. An unexpected arrival from Ireland in New South Wales in 1817 was a Cistercian priest, Fr Jeremiah O’Flynn. He had a chalice and vestments supplied by the Congregation of Propaganda in Rome. He was welcomed in Van Diemen’s Land, where he celebrated Mass in public, and officiated at baptism and marriages. But in New South Wales he was not well received, and he was lodged in jail and within a year of his coming he was on his way home.

Fr John Joseph Therry from Cork and Fr Philip Conolly from Monaghan arrived early in 1820, and gave new hope to the Catholic community in the colony. Fr Conolly served 2 years in Port Jackson before moving to Van Diemen’s Land to minister to the convicts. Fr Therry’s greatest ambition was to have a church built for his congregation and this he finally achieved with the aid of two former prisoners, James Meehan, who chose the site, and Francis Greenway, who designed St Mary’s.

Governor Macquarie laid the foundation stone of St Mary’s Chapel in 1821 on the site of today’s Cathedral, the first land granted to the Catholic Church in Australia. But it was destroyed by fire in 1865. The initial section of the Gothic Revival style Cathedral was opened in 1882. In 1928 the building was completed, but without the twin southern spires proposed by the architect. By the entrance steps are statues of Australia’s first Cardinal, Cardinal Moran, and Archbishop Kelly who laid the foundation stone for the final stage in 1913. The crypt’s Celtic inspired terrazzo mosaic floor took 15 years to complete. In 1857 more than one-third of Catholic marriages in New South Wales were celebrated in St Mary’s Cathedral, and of the 316 brides that year, 259 were Irish born.

The laying of the foundation stone of Sydney’s second Catholic Church, St Patrick's, Church Hill, took place in August 1840, on a site donated by William Davis, a veteran of 1798, who had become a wealthy man. Daniel O’Connell achieved Catholic Emancipation for Ireland in 1829, with the result that the Catholic Church was free to develop and expand without hindrance. In 1833 the Irish population of NSW was estimated to be about a third of the total population. Their spiritual welfare was in the care of the Vicar General and two priests, and it was hoped that 4 more priests would be available in the following year. St Mary’s Cathedral was not yet completed, but chapels at Campbelltown, Maitland and Parramatta were opened. Government grants were given towards Catholic schools, which were regulated after the manner of the schools in Ireland. This improvement in the status of the Catholics was mainly due to Governor Richard Bourke who arrived in 1831. He was from Dublin and he was a humane and reforming officer who soon found himself unpopular with both the officials and settlers. His Church Act in 1836 confirmed the principle of religious equality, and government funds were made available for Church buildings.

All these activities brought massive demands on the Catholic Church. Australia was seeking priests and nuns from Ireland to develop its church there. Ireland responded magnificently. It is impossible to tell the full story, but a few examples may help. Between 1846 and the close of 1900, no less than 450 priests went from All Hallows College to Australia. In terms of effective ministry, they must have given close to, and probably more than, one-third of all the service given by Irish Priests in Australia during the 19th century. In 1838, Dr Ullathorne brought back from Europe a group of priests and students to accompany him on his mission, and four Irish Sisters of Charity, whose superior and founder was Mother Mary Aikenhead. They commenced work at the factory for female convicts in Parramatta, where they found that 400 of the 600 prisoners were Catholic. A school was opened for the children, and it was arranged that a priest would visit to administer the sacraments, and within a year 200 were confirmed. In 1888, Cardinal Moran of Sydney, formerly Bishop of Ossory, arranged for nine nuns from the Sisters of Mercy at Callan, Co Kilkenny to set up a mission at Parramatta. From a broken-down residence, teaching in sheds protected in part only by sugar bags along the sides, grew a great network of new schools, convents and orphanages, parish and hospital visitations.

One is at a loss when it comes to assessing the contribution of these hundreds of priests and nuns who today lie buried in convent and other cemeteries all over the great continent. The motivation of their life-work was not achievement or ambition, but vocation, a sense of God, of a call from God, or responsibility before God. They left behind them their mark on the fabric of Australian life and culture, and a Catholic Church distinctly Irish.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Catholic Church in Australia became aligned with the Labor Party. The events in 1916 in Ireland shocked Australia. The conscription referendum of October 1916 was perceived by its leading advocates as a test of the British loyalty of the electorate. A similar reaction followed the defeat of the second conscription referendum in November 1917. Ireland and Australia maintain normal trade and diplomatic relations.

Irish Women in Australia

Very little is known about the Irish women in Australia, except for the grossly distorted reports of the officials and the media. During the whole of the transportation period, a quarter of all the Irish transported were women. The 1841 census for New South Wales showed that there were approximately 4,000 women to 40,000 men.

Various schemes were promoted to redress this imbalance. Under the Orphan Emigration Scheme a total of 4,175 female orphans from the workhouses were transferred to Australia. All of them were volunteers, eligible candidates in the selected union being invited to put their names forward. All the females found employment immediately. The official report was overwhelmingly favourable to the orphans. They were described as being orderly, obedient and industrious. This scheme ended in May 1850.

The work of Caroline Chisholm on behalf of the Irish women in Australia is acknowledged. She worked tirelessly with the Irish Sisters of Charity to improve the lot of the workers at the female factory at Parramatta. When a man came to the factory to find a wife, the women were offered an opportunity to meet him. They would have been instructed by the nuns and they would have received the sacraments. The women were summoned to the factory parlour where the prospective groom interviewed them. He chose the one he fancied and they were allowed to have a private conversation. If they agreed to marry, the appropriate clergyman was sent for and the knot tied. These were the women who pioneered the Australian bush, the women who brought stability of family life to the convict colony, the women who worked with the men to develop and build this colony. They were partners of the men who opened up the farms and settlements, and developed the towns and villages. They took an active and energetic part in the way in which society developed. Most importantly, it was the direct influence and example of these Irish women, which significantly affected the nature and characteristics of the first generation of boys and girls entitled to call themselves Australians by birth.

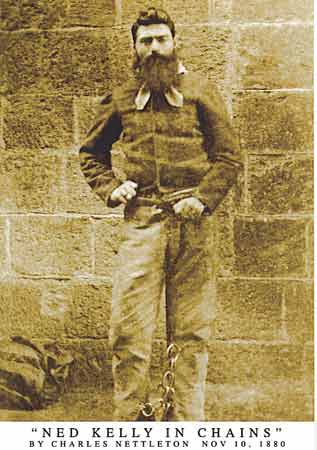

Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly

There is no need to introduce Ned Kelly to Australia where he is already a folk hero and a legend. Many films and documentaries have been made about him. Several books have been written about his exploits, and a tourist industry has been built around his short life. In the first half of the 19th century the best land was owned by the wealthy squatters, with small plots of very poor soil, known as Ôselections’, being offered to the Irish. The Irish felt cheated and degraded. Who would have heard their cry of rage and desperate fury but for Ned Kelly?. The Irish were upstarts in the colonies and should therefore be put down, shown their place. Ned Kelly simply lashed back at his tormentors. Here is his story in outline details only.

John Kelly was born on February 20th, 1820 in Killenaule, Co Tipperary. He was transported to Van Diemen’s Land, and when he was free he moved to New South Wales, where he married the daughter of an Irish emigrant. She was Ellen Elizabeth Quinn born in 1832 in Co Antrim. They were married on November 18th, 1850 in Melbourne, Victoria. Their son Edward (Ned) Kelly was born on December 28th, 1854 in Beveridge, Victoria. John Kelly died on December 27th 1866, and his wife died on March 27th, 1923. Ned was introduced to the violent life of bushranging by Waterford-born Henry Johnston, who was also known as Harry Power.

Ned was the eldest of 8 children, and he was just 12 years of age when his father died, and his family settled near relatives at Greta, 240 kilometres northeast of Melbourne. He was just aged 16 when he was convicted of receiving a stolen horse, and he served three years in jail before being released in 1874. In April 1878, a police officer named Fitzpatrick accused Ned’s mother of attacking him, and Ned of shooting him in the wrist. Some versions of the event state that Fitzpatrick assaulted one of Ned’s sisters first. Mrs Kelly was imprisoned for three years and a £100 reward was offered for the capture of Ned.

From that time on Ned and his brother Dan kept to the bush. On October 26th, 1878, together with friends Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, they came across police camped at Stringy Bark Creek. In the ensuing fight three police officers were shot dead. The reward for Kelly and his gang rose to £2,000 and later rose to an amazing £8,000. They robbed a bank at Euroa, and on February 10th, 1879 they raided the bank at Jerilderie. They detained 60 people in the dining room of the hotel next to the bank. Ned brought with him a written statement, his autobiography, his attempted self-justification, a document of 8,300 words. He wanted to have it printed in the Jerilderie newspapers but the editor could not be found. As well as getting the money, he wanted to prove that he was right.

On June 27th, 1880, the gang shot Aaron Sterritt dead. That was the penalty for informing on the Kelly gang. Later that day they took possession of a hotel in Glenrowan, and cut the telegraph wires and forced the railway workers to rip up the line. They were wearing suits of armour, which did not protect their arms and legs. A warning was given and the train stopped at the station, and a bitter gun battle took place with the police laying siege to the hotel. Joe Byrne was shot dead by a police bullet. The police set fire to the hotel and Dan Kelly and Steve Harte were burned to death. Ned was captured and taken to Melbourne, patched up, hurriedly tried and sentenced to death. At 10 am on November 11th, 1880, Ned Kelly was hanged in the old Melbourne jail, where he is buried in an unmarked grave. Go ndeana Dia trocaire ar a anam. May he rest in peace. Amen.

Famous Irish People in Australian History

Ned Kelly (1854-1880) A legend in his own lifetime.

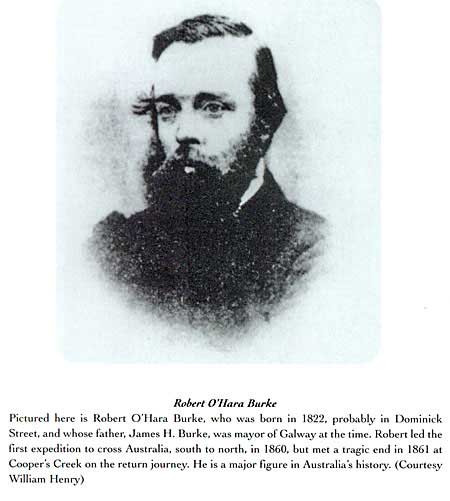

Robert O’Hara Burke (1822-1861) He led the first expedition to cross Australia, south to (1822-1861), north in 1860.

James Meehan (1774-1826) Resonsible for almost all the land surveys and road and town plans in New South Wales. Meehan Valley in Tasmania bears his name.

Edward Eagar 1787-1866 Introduced Methodism to Australia.

William Charles Wentworth (1790-1872) He campaigned for a reform of the Constitution and of the legal system. He supported the Irish in their call for more rights in the colony.

Archbishop Daniel Mannix (1864-1963) Archbishop of Melbourne in 1917. He gave a voice to the Irish.

Cardinal Francis Patrick Moran (1830-1911) First Cardinal of Australia.

Fr. James Dixon (1758-1840) He celebrated the first public Mass in Australia on May 15th, 1803.

Sir Charles Gavin Duffy (1816-1903) His Land Act 1862 saw Victoria through Irish eyes.

J.H. Scullin (1876-1953) In 1930 as Prime Minister of Australia he paid a brief visit to Ireland.

Governor Richard Bourke (1777-1855) His Church Act in 1836 confirmed the principle of religious equality.

Paddy Hannan (1840-1925) A Clare man, he discovered gold in Kalgoorlie.

Thousands of Irish people contributed to the culture and history of Australia. The above is just a short list.

Epilogue

At the outset it must be said that the Irish who were transported and those who went to Australia as free emigrants were exactly the same kind of people. Invariably the men were rounded up and transported, with their wives and families joining them later on. We must treat with the proverbial Ôgrain of salt’, the reports of the colonial officials and medida. These reports clearly outlined the contempt and prejudice with which the Irish were treated in the early years. But it was conceded that the Irish were different from the English, Scots or Welsh.

When the Irish settled into their new places, they rarely offended anyone. Tolerant of human weakness, they presented an independent and democratic voice in a community which had inherited its values from 18th century England. They understood the frailty of human nature. Their contribution to the new society was significant.

As I was writing this last section, I received an email from Suzanne Rutschmann, Sarsfield Estate Vineyard and Winery, 345 Duncan Road, Sarsfield 3875, Australia. They are a small boutique winery located at Sarsfield, Australia. The town of Sarsfield has been named by Charles Marshall after General Sarsfield, a distant relative. Sarsfield is located in the south-eastern corner of Victoria, about 400km west of Melbourne. Her email address is sarsfieldestate@bordernet.com.au

Finally may I conclude with a few lines from Oliver Goldsmith’s (1728-1774) poem ‘The Deserted Village’:

“Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay:

Princes and Lords may flourish, or may fade;

A breath can make them, as a breath has made;

But a bold peasantry, their country’s pride,

When once destroyed, can never be supplied.”

Bibliography

Botany Bay - Con Costello

Australia and Ireland Bicentenary Essays, 1788-1988 - Colm Kier___Änan

The Irish in Australia - Patrick O’Farrell

The Convict Ships - Charles Bateson

The Fatal Shore - Robert Hughes

The Oxford Companion to Irish History - S.J. Connolly

This Great Calamity - Christine Kinealy

True History of the Kelly Gang - Peter Carey

A History of Manchester - Stuart Hylton

Galway in Old Photographs - Peadar O’Dowd

The Irish Empire - Patrick Bishop

The Manchester Martyrs - Paul Rose

Acknowledgments

Due to illness this story would not be possible without the help of a great many people, particularly my family. My wife Elizabeth wrote the script out in longhand, and Maria, Emma and Judy typed everything onto the computer. Eoin, Mark and Pamela helped at all stages. Ann Harney did her usual brilliant job. She visited Ireland and Portumna in March 2005. Tony McNamara provided the pictures of the Manchester Martyrs and Orla Flannery took the picture of their monument in Manchester. Philippa Coleman sent me books from Sydney. Fr Kieran O’Rourke C.C travelled to Wexford to take photographs. Tom Felle provided the inspiration, the book and the map. Jack Lynn, John Culhane, Robert Lambert and Nicky Cowman, all from Wexford, supplied the information and pictures about Fr Dixon. The libraries at Portumna, Tullamore and Cork were extremely helpful at all times. Fergal and Larry Duffy did all the scanning and arranging the pictures on discs. John Wogan-Browne in Melbourne and Stephen Nevin in London advised me on some details of history.

Links:National Archives Ireland

National Archives Australia

Jim Barry Wines

Copyright @ Sean Ryan 2006