Introduction

The primary purpose of writing this story is for the benefit of students,

researchers and historians. It is a huge subject and I can only barely

discuss it in broad outline. I have given at the end a valuable reference

list and details where research and original material may be found. The

writings of Micheline Walsh are especially recommended. Her father was the

first Ambassador to Spain in 1936 and her research is very detailed and

guides the researcher as to where material may be found. When this lady

died a few years ago all her material was purchased by a mutual friend named

William A. Miailhe de Burgh and he also has offered £200,000 worth of books

based on the Wild Geese and the Burke families for a library in Portumna

Castle. So far the library has not materialised. The books by

R. A. Stradling and Dr. Brendan Jennings are highly recommended.

The Spanish Empire at war in the 17th Century

In 1492 Ferdinand and Isabella sent Christopher Columbus on a voyage that

took him to America. Spanish explorers discovered the new world. In the

following 50 years Spain controlled the Americas, Mexico, the West Indies

and Africa. They also controlled part of France, most of Italy, Portugal,

the Canary Islands, the Philippines, the Island of Guam, the Balearic

Islands, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Gibraltar. The Spanish Netherlands is dealt

with in a separate section below.

At the height of its fame at the end of the 16th Century, the Empire began

to decline. In 1588 the Spanish Armada of 130 ships was beaten by the

English and was forced to return by the North sea and many ships were blown

ashore in Ireland. Only 67 reached Spain. The defeat at Kinsale in 1601

was a further blow to the Empire.

It was necessary for Spain to maintain armies in all these countries, which

was an impossible task. We will concentrate on Europe where England, France

and Spain were battling for control. These three countries were constantly

at war and as we see below the Netherlands was fighting an 80 year war for

independence. Portugal was also fighting a 30 year war (1638 - 68) for its

own independence. Provinces of Italy were in revolt such as Mantua,

Piedmont, Lombardy, Naples and Palermo. In Spain Catalonia was in revolt

and the town of Lerida was under siege from 1641 - 47 until the French

withdrew. The French also were attacking towns on the border with the

Basque area. Many towns in Catalonia such as Barcelona, Salces etc. were

also under siege. There were also wars in Levant and Aragon.

Because of the many wars that Spain was engaged in at the one time there

came about a huge shortage of recruits for the army. Many of the

traditional areas of recruitment such as Castile, Navare were reluctant to

supply any more recruits. Also, many other areas would not agree to

conscription. The plague which was dominant in Europe in the middle of the

17th century badly affected Spain where over 500,000 of its people died in a

few years. Consequently the council of war began to search for mercenaries

from other countries to keep its army up to full quota. Germans, Italians

and Walloons were engaged but because of the reputation of the Irish

it was planned to seek a regular supply of soldiers for its armies from Ireland. Accordingly, contacts were made with the English authorities in Ireland and with the Confederation of Kilkenny in order to obtain licences for recruitment. This was done by means of official contact at diplomatic level and by administrators and contractors.

Ireland in the 17th Century

Ireland was ruled by England for 800 years. Like all countries yearning

for its freedom there were many insurrections, revolutions, famous battles,

heroes and martyrs. The following then are the main events which led to the

exodus of many thousands of Irish soldiers and their families to France,

Spain and other European countries. 1601-03 Kinsale, The Treaty of Melifont,

Retreat of O'Sullivan Beare, Rebellion of Cahir O'Doherty. 1607 The Flight

of the Earls. 1609 The Ulster Plantation. 1625 The Graces-payments by Irish

Catholics for concessions. 1633-1640 Wentworth. 1641 The 1641 Rebellion.

1642-1650 The Confederation of Kilkenny, Oliver Cromwell, The Cromwellian

Land Settlement, The Down Survey. 1660 The Restoration. 1661 Act for the

Settlement of Ireland - soldiers and adventurers confirmed in their lands -

persecution of Irish Catholics. 1681 Oliver Plunkett - convicted on false

evidence - executed in Tyburn. 1688 The Siege of Derry. 1689 James II

landed in Kinsale. 1690 The Battle of the Boyne - July, The First Siege of

Limerick - August. 1691 Siege of Athlone, Battle of Aughrim - July,

Second Siege of Limerick, The Treaty of Limerick, The Flight of the Wild

Geese. 1692 - 1697 The Parliaments of 1692 and 1697 penalised Irish

Catholics - breach of Treaty of Limerick - Penal Laws had begun.

The Main Story

The Spanish Monarchy and Irish Mercenaries.- The Wild Geese in Spain

1618-68.

This is the title of an excellent book written by R.A. Stradling, a senior

lecturer in University of Wales College of Cardiff

As we see from above Spain was desperate for new recruits for its war

machine. The situation in Ireland was perilous. In July 1640 an army of

10,000 had been collected by Strafford and it was based in Carrigfergus,

and 5,000 more were collected in various parts of Ireland. Olivares of

Spain contacted the English Parliament with a view to obtaining a licence

for transferring of this army to Spain, but negotations dragged on for

over twelve months. This army was originally intended to be transferred to

the English mainland but the need for same did not arise so it was decided

to demobilise it. This army mutinied and became the beginning of the

famous 1641 Rising which lasted for 12 years and was put down with severity

by the English.

Oliver Cromwell arrived in Dublin in May 1649 and in the course of his march

through Ireland people deserted in his path or otherwise sought escape from

certain death. His infamous ultimatum to the Irish people "To Hell or to

Connaught" will never be forgotten in Irish history. In a twelve month

march accompanied by blood, fire, plague and persecution he eliminated

Gaelic - Catholic Ireland which did not recover for almost 3 centuries. In

May 1650 Cromwell left Ireland at Kinsale.

The Spanish Crown issued contracts to officials, agents and contractors

for the delivery

of Irish recruits. These contracts specified the number of men, the amount

of money and the ports of delivery. These people then had to travel to

Ireland and begin negotiations with English authorities in Dublin and the Catholic Confederation of Kilkenny. There were many difficulties in making contacts, procuring ships and delivery of money from Spain. Most of the contracts provided part of

the contract money in advance to meet ongoing expenses. A further

difficulty was that the French were also in the market for Irish recruits

and there was much intrigue and espionage going on at all times. The whole

episode presented a massive dilemma for all concerned. England was

providing recruits for the army of its enemy while Spain was doing business

with a heretic enemy, which was persecuting fellow catholics and who had the

blood of martyrs on its hands. The Confederation could ill afford to lose

its army. The main contractors were Cardenas, Foisotte, De la Torre,

Berehaven (Dermot, son of O'Sullivan Beare), Mayo, White, Patrick,

Walters, Skinner, O'Brien and Gouvernour.

As the leaders and rebels surrendered they were offered terms and their

lands were confiscated. Many requested transport to Spain where they

thought they could begin a new life. The ports of departure were mainly

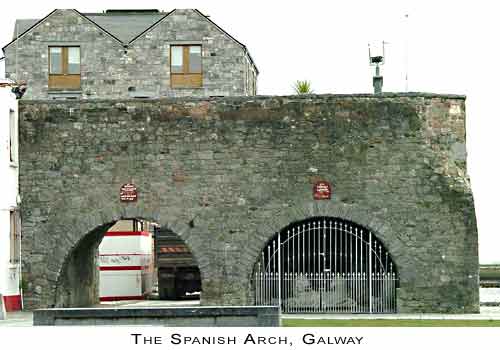

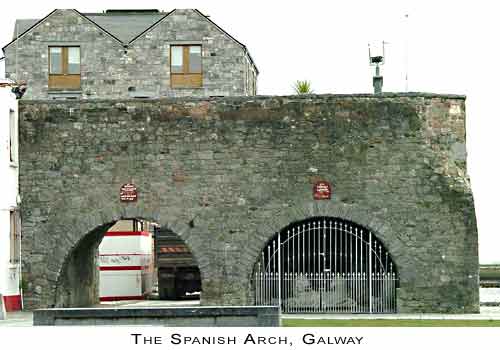

Galway and Waterford. Galway served Connaught and Ulster and Waterford

served Munster and Leinster. They gathered up their papers, goods and

chattels, and were force marched to the ports of departure. They were

packed like cattle on the ships which were of inferior quality. Being

loaded as they were they contacted all kinds of diseases. Many died on the

journey and had the dubious distinction of burial at sea. The journey was

supposed to take 15 days but with unfavourable winds and enemy ships it

often took much longer. Private illegal ships were also a danger as they

attacked the official ships. Conditions on board these illegal ships were

very bad indeed and it was said that there was no problem in tracking them -

just follow the dead bodies floating in the water. All the ships landed at

the ports on the northern coast of Spain such as La Coruna, Santander,

Laredo, San Sebastian, Pasajes and Bilbao. The one exception was Cadiz on

the southern coast.

As the leaders and rebels surrendered they were offered terms and their

lands were confiscated. Many requested transport to Spain where they

thought they could begin a new life. The ports of departure were mainly

Galway and Waterford. Galway served Connaught and Ulster and Waterford

served Munster and Leinster. They gathered up their papers, goods and

chattels, and were force marched to the ports of departure. They were

packed like cattle on the ships which were of inferior quality. Being

loaded as they were they contacted all kinds of diseases. Many died on the

journey and had the dubious distinction of burial at sea. The journey was

supposed to take 15 days but with unfavourable winds and enemy ships it

often took much longer. Private illegal ships were also a danger as they

attacked the official ships. Conditions on board these illegal ships were

very bad indeed and it was said that there was no problem in tracking them -

just follow the dead bodies floating in the water. All the ships landed at

the ports on the northern coast of Spain such as La Coruna, Santander,

Laredo, San Sebastian, Pasajes and Bilbao. The one exception was Cadiz on

the southern coast.

Some of the port authorities refused permission for the ships to dock. They

were concerned about the health of the population of their town because

they feared that the Irish were carrying contagious diseases and the plague.

The Galway ships were the most suspect as the plague was particularly

severe in Connaught. Galway had good trading relations with Spain, and it

was suspected that the plague came from Spain in the first place. Some were

allowed to take on water and had to move to find another port. The

passengers were almost naked, starving and sick. As they came ashore the

fittest men were marched off to be prepared for the battle front. The sick

were treated with the best medicine available and the remainder were marched

to houses where they were allowed to rest before being put into training.

All were fed, clothed and allowed to recover from their ordeals.

In Autumn 1641 300 men were the first to reach Spain direct from Ireland and

they sailed into La Coruna. Because of the difficulty in negotations only

a small trickle of recruits arrived from Ireland during the following five

years, but when the Cromwellian army reached its height of destruction in

Ireland the trickle became an avalanche. Mr Stradling informs us that

22,531 people arrived in Spain between 1641 and 1654 and if we add in the

women and children a figure of 40,000 emerges. All the soldiers were

accommodated in the principal towns in the northern ports of Spain, but

when these became overcrowded they were transfered inland to such

towns as San Vicente, Santander, Laredo and Castro Urdiales. They were divided up into small groups, so that they would not be a burden on any one community. The

local people were expected to supply them with "hearth, salt and candle". When all was ready they were marched to assembly points in the major towns such as Zaragoza and then

they were marched to the various battlefields in Portugal, Catalonia,

Aragon, Bordeaux etc. They were billeted during their journey at

convenient small towns and villages and the normal practice was to feed

them in the town square and then march them to their accommodation. As the

peace treaties with Portugal, France, England and Catalonia became

effective, the movement of fresh recruits from Ireland diminished

accordingly and a moratorium on all recruitment was declared on the 21st of

August 1653. The last ship arrived in Galicia in November 1654.

In all the battles the Irish fought with great bravery and courage. At the

battle of Montjuich outside the walls of Barcelona in 1641 the Earl of

Tyrone was killed at the head of his army. In 1642 at the battle of

Tarragona they were defeated by the French and on the return journey

O'Donnell was intercepted and badly mauled by the French navy. O'Donnell and

hundreds of his men were killed and many others were captured. Both the

regiments of Tyrone and Tyrconnell disappeared into oblivion. The regiment

of O'Donnell claimed its place in Spanish history as the most valuable Irish

regiment ever to serve the Spanish monarchy. During these 14 years some of

the Irish deserted and became fugitives or deserted to the enemy or joined

the Spanish Navy. The women and children suffered badly also and became

beggars on the streets of Madrid and other large towns. They depended on the

charity of the Spanish people and many entered convents. With the deaths of

O'Neill and O'Donnell and the return of Fitzgerald and other leaders to

Ireland, the Irish became leaderless and reduced very much in numbers. As

the army was disbanded the soldiers returned to their families and sought to

embrace the Spanish way of life. They adopted Spanish names and became more

Spanish than the Spanish themselves. The pull of home tormented many and

they returned to the auld sod. The officers and their families achieved some

standing in Madrid whilst the nobility and chieftains married into Spanish

noble families. These noble people like the O'Neills, the O'Donnells and

the O'Sullivan Beares later appeared in the political and military history

of Spain. They preserved links with their Irish heritage and to this day

their names appear prominently in the register of membership of all the

great Orders of Spain.

The Wild Geese in Spanish Netherlands.

Belgium and Holland (Netherlands) are collectively known as the Low

Countries. Flanders is an area in the Northern half of Belgium and the

people who are known as Flemish speak Dutch. Walloonia is an area in the

Southern part of Belgium and the people there are known as Walloons and

speak French.

In the 1300's the French Dukes of Burgandy won control over the Low

Countries, and in 1516 Duke Charles of Burgandy also became King of Spain,

and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. His son Philip 11 of Spain inherited

the Low Countries in 1555. In 1568 the nobles of Holland rebelled against

his harsh rule and they were led by William 1 Prince of Orange. On July 26,

1581 the northern provinces declared their independence from Spain and in

1648 Spain recognized Dutch independence. Belgium however remained under

Spanish rule until 1713 when it was given to Austria as part of the

settlement of the War of the Spanish Succession. Belgium became a part

of France in 1795 and in 1830 achieved full independence.

The same circumstances applied to the Irish who went to fight in the Spanish

Netherlands as to those who went to mainland Spain. Spain preferred to have

the Irish trained in the Netherlands before using them in the army on the

Iberian peninsula. In actual fact there was a constant exchange of troops

between the Netherlands and Spain.

Historians agree that in 1585 Sir William Stanley recruited a regiment of

Irish to fight in the Netherlands and in 1587 this Anglo Dutch army of 1,000

Irishmen defected to Spain. Irishmen were part of the army of Spain against

the United Provinces in 1621 and also in the great war between Spain and

France in 1635. In 1623 Owen Roe O'Neill had 1300 men in the Spanish

Netherlands. Irish and Italian soldiers were treated on an equal footing as

the Spanish. In 1635, 7,000 Irish were present in the Low Countries, and

were organised into 4 units under Owen Roe O'Neill, Thomas Preston, Hugh

O'Donnell and Patrick Fitzgerald, but only a third of these could be

accounted for in 1639. Only 150 Irish men arrived in Flanders in 1640. The

sieges of Arras and Gennep in 1640-41 brought them undying fame.

Owen Roe O'Neill returned to Ireland in 1642 to fight the catholic cause and

many of his troops went with him. In 1638 the regiments of O'Neill and

O'Donnell were transferred from Flanders to Spain and these became the first

Irishmen to fight as a unit in Spain. They fought at the relief of

Fuenterrabia in 1638, and in 1639 - 40 they fought with great bravery at the

siege of Salces on the Catalan frontier. Owen Roe O'Neill remains the most

distinguished Irish soldier ever to serve the Spanish Monarchy.

Mr Stradling states in his book that over 17,000 Irishmen were transfered

from Ireland to Flanders between 1623-1665. The majority of the officers and

men serving in the Spanish Netherlands in the 1620's were transferred to

Spain sometime between 1638 and 1662. Many Irish soldiers in the

Netherlands in 1662 opted for other employment rather than be transferred to

Spain. The army of Flanders suffered badly from the transfer of men to Spain

and during the ten years from 1636 -1646 the Irish contingent declined from

7000 to only 200. All the Irish Companies in the Netherlands were gradually

reduced, so that in 1665 only 37 men were left in the army of Flanders. The

Treaty of Portugal (in 1668) put an end to all the recruitment of soldiers

from Ireland to Spain but export to Flanders was periodically renewed.

The Flight of the Earls 1607

When James 1 became King in 1603 the Irish Catholics hoped for an easing of

their disabilities. James was the son of a Catholic mother. However he was

not in favour of removing any religious disabilities. Hugh O'Neill's

position had steadily worsened. Mountjoy treated the Northern chiefs with a

certain sympathy. Chichester his successor was not prepared to do likewise.

Charge after charge was brought against O'Neill. Chichester was bent on

destroying the Ulster chiefs. In 1607, Hugh O'Neill, Rory O'Donnell and some

other chiefs sailed from Rathmullan, with their wives and families and left

Ireland forever. Rory O'Donnell and his brother Kaffar died in Rome within a

year. Hugh O'Neill's son, Hugh died soon afterwards. The Earl lingered on

until 1616 hoping one day to return to Ireland. He is buried in Rome beside

his son and the two O'Donnells.

O'Sullivan Beare in Spain

Beare is a beautiful area in West Cork. It gets its name from the Spanish

Princess Bera, the wife of the first king of Munster. After the Battle of

Kinsale where the Irish and the Spanish were defeated by the English in

1601, most of the Irish Chieftains surrendered but O'Sullivan Beare

considered that if he could join up with other Chieftains perhaps he could

continue the war. Accordingly he set out on a epic march from Glengariff to

Leitrim on the 31-12-1602 to 14-01-1603, with one thousand followers, but

only thirty five arrived at O'Rourke¹s Castle in Breffni. He rested there

for a few weeks before attempting to join O'Neill. When he reached O'Neills

encampment on the shores of Lough Neagh he found that O'Neill had already

left for Mellifont to submit to the Lord Deputy Mountjoy. This was March

1603. O'Neill and the other Chieftains were given back some of their

territory under surrender and regrant, but O'Sullivan was declared an

outlaw.

Philip III of Spain sent a ship for him in the spring of 1605, and he

escaped with a few hundred of his followers and was graciously received. He

was made a Knight of the Order of St. James, and of the Order of Santiago,

and Count of Berehaven. He founded the Irish college of Santiago de

Compostella and also was involved with the Irish college at Salamanca. He

was killed in a fight in the year 1618 and his tomb is in La Coruna in the

Church of Las Tres Marias. The family settled in La Coruna where most of

them were buried. His family became influential in the military and

establishment in Spain. His nephew Don Philip O'Sullivan was an advisor to

the Spanish crown, and was a noted historian. His son Dermot became a key

figure in the Spanish Court and was sent back to Ireland to recruit Irish

soldiers for the Spanish army.

The O'Neills in Spain

This is the title of a small book written by Micheline Walsh in 1957. The

book is exceptional as the notes are immensely detailed. She gives the

sources of her information in minute detail.

In 1600 Henry O'Neill settled permanently in Spain. He was 13

years old and the

second son of Great Hugh O'Neill and his second wife. In 1605 he was given

the colonelcy of an Irish Regiment in the service of Spain. He died on

25th August 1610 at the age of 23. He was succeeded by John, another son of Great Hugh, who was educated by the Irish Franciscans in Louvain. Spain recognised Great

Hugh¹s title of 2nd Earl of Tyrone translating it by "Conde de Tyron". Officially John was the 3rd holder of this title. John received many decorations in his long

military career for Spain. In January 1641 with the Spanish army, he

approached Barcelona and in the morning of the 29th January with his

regiment of Tyrone, he attacked the Fortress and was the first to be killed

in the assault. He was the last surviving son of Hugh O'Neill.

He was succeeded by his natural son Hugh Eugenio who was only 7 years old

at the time. He was made a Knight of Calatrava in 1644. He served with his

Irish Regiment of infantry in Catalonia and he died at the end of October

1660 and he was the last male representative of Great Hugh O'Neill. The

genealogy, military and social history of the O'Neill's in Spain are

precisely dealt with by Micheline Walsh in her various publications.

It is remarkable that for almost a century the Irish regiment of Hibernia

in Spain was never without at least one O'Neill among its senior officers.

At the formation of the regiment in 1709 the senior captain was Arthuro O'Neill. The story of the O'Neills of Spain deserves much time. Despite confiscation of property,

imprisonment and persecution at home, and on the continent, the trailing by

spies, the hounding by English agents and persistent diplomatic pressure on

their Spanish protectors, these O'Neills still rose again and re-established

their name and family as we have briefly indicated.

Of course in this connection we must not forget the generosity of Spain

which sheltered them in need, and extended to them all the rights of Spanish

subjects, with all the opportunities for advancement possessed by the native

Spaniard. But despite all this there remained the inevitable disadvantages

and hardships of being strangers in a strange land. Yet each O'Neill

generation of the four centuries from 1600 to the present day has

distinguished itself with a striking and persistent regularity. For their

loyal services they have been rewarded with titles of nobility and

knighthoods of the most select orders; they have been leaders in business

and the arts; they have reached the rank of Army General on innumerable

occasions; they have been Captains General and Governors of provinces at

home and in the New World; they have been Presidents of the High Court and

on at least three occasions, in three different centuries, they have been

members of the Supreme Council of War. The story of these O'Neills is one

of generosity and noble protection on the part of Spain and sustained

achievement on the part of every generation of the family.

The O'Donnells in Spain

Hugh O'Donnell (Red Hugh) was the son of Hugh Dubh and Finola

(MacDonnell-Ineen Duv). His father was loyal to the English but his mother

was strongly nationalist. She imbued her son with a like spirit. The English

wanted to capture him, and by a trick he was captured and imprisoned in

Dublin Castle in 1587 for over 3 years. In 1590 he and a companion escaped,

but they became fatigued and were soon captured and brought back to the

Castle. In 1592 he escaped again with Henry and Art O'Neill and made their

way to Fiach Mac Hugh O'Byrne in Glenmalure in the Wicklow Mountains. He

joined with the other Irish chieftains in the war against the English, but

were finally defeated at the battle of Kinsale in 1601. He made his way to

Spain to seek help from Philip II but

he was taken ill and died at Simancas in 1602. He was buried in a

monastery of St

Francis in the Chapter House in Valladolid. For many centuries it was

thought that he

was poisoned by an agent whom Carew claimed to have sent there for

that purpose.

Now it is believed that he died from the bubonic plague.

The distinguished military dynasty of O'Donnell - Counts of Abispal and

later Dukes of Tetuan - produced several generations of celebrated

commanders, and a Prime Minister in the 19th century. One of the principal

streets in Madrid is named Calle O'Donnell - a fitting tribute to this

illustrious family.

The Irish Franciscans in Spain

This subject is included to demonstrate that Ireland and Spain were Catholic

countries and that Spain was helping Ireland to maintain its Catholic

heritage. The Irish at this time believed that they were descended from the

Celts of Galicia which is a province on the North Western coast of Spain.

They believed they were descended from the followers of

Milesius and his son who were the first Celts to colonise Ireland about 800

BC.

All the ships that left for Spain and the Netherlands also included many

priests from the various religious Orders. They were normally dressed the

same as the soldiers and endured the same hardships. As part of the

cementing of the relationship between the Franciscans and the Spanish

Government Ireland accepted a Spanish Franciscan as a Bishop of Dublin and

from then on Spanish money and diplomatic services were available to the

order.

In the middle of the 17th Century the Irish Franciscan house at Louvain was

established and a seminary in Santiago was established by O'Sullivan Beare.

In the 1620's when the war against the Dutch was renewed it was the

Franciscans who acted as priests to the Irish Regiments. The Franciscans

were the most powerful Order in Spain and when money was scarce in the

1640's Philip IV continued to subsidise Louvain and the other colleges. The

Franciscans returned the favour when acting as couriers and conveyers of

Madrid's international policy. During the persecutions of the 1650's the

Franciscans continued to support the Irish Catholics at home and abroad.

Their presence among the fighting men in Spain was welcome as they were able

to inspire heroic deeds on the battle field and on the march. They were able

to interpret the Spanish language for the native Irish and thus act as

mediators.

The Franciscans were respected in Cantabria where they had several

foundations. The most energetic of the Franciscans living in Spain was Fr.

Luke Wadding. The Franciscans acted as postmen for the Officers in Spain

bringing news from Ireland which filled them with nostalgia. As the

avalanche of Irish stopped, the influence of the Franciscans with the King

also receded.

Spanish Knights of Irish Origin

Spanish Knights of Irish Origin. This is the title of a book in four volumes

by Micheline Walsh. It is written in Spanish, and contains the genealogy of

more than sixty Irish in Spanish regiments who were decorated with military

orders of chivalry or knighthoods. These are the orders of Santiago,

Calatrava, Alcantara, Montesa and Carlos III. Along

with the genealogy of the knights are long lists of their Irish

sponsors, about 25 in

number, giving their place of birth in Ireland.

Some of the most familar

names who were

decorated are as follows.

- Donal O' Sullivan Beare (1560-1618), whose

story is given

above

- Richard Wall (1694-1778) who became a Minister for Foreign Affairs

and leader of the government of Spain in 1754, a post which he held for nine

years, under two successive Kings.

- James Francis FitzJames Stuart (1696-1738). The Duke of Liria, as he was

known for most of his life, was born at St. Germaine-en-Laye in France and

was the son of James FitzJames Stuart, 1st Duke of Berwick, and of Honora

Bourke of Portumna, Co. Galway

- Felix O'Neill (1720-1796)

- Arturo O'Neill (1736-1814)

- Leopoldo O'Donnell (1809-1867)

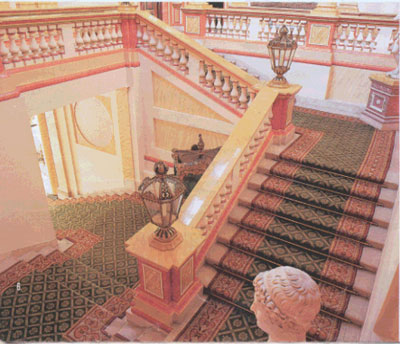

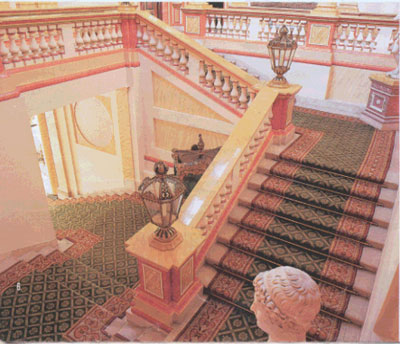

Palace de Liria Madrid |

The Main Entrance to

the Palace

|

Famous Irish Regiments in Spain

This subject is covered very well in the publications of Walsh, Hennessy,

Stradling and other famous historians. In the beginning the Irish were

amalgamated with the other mercenaries from other countries and had no

particular identity. Gradually, however they began to assume their own

identity, and became assembled with the ad hoc regiments of O'Reilly, O'Brien, Gage, Murphy, Coghlan, Dugan and Dempsey, and also the regiments of O'Neill and O'Donnell. The first Irish regiments taken into the Spanish service were those of the Marquis of Castlebar and Dermot MacAuliffe, both of whom received their patent of creation from the King of Spain at Zaragoza on 1st November, 1709. Eventually they received the

permanent title of Hibernia and Ultonia respectively. Vendome received the

title of Limerick, Comerford that of Waterford and Waucope that of Irlanda.

The regiments of Hibernia, Ultonia and Irlanda achieved particular renown

fighting for Spain at the battles of Zaragoza (1710), Brihuega and

Villaviciosa. They also fought at the sieges of Barcelona (1714) and

Gibraltar. They fought against the Austrians from 1742 - 1748 and this army

was commanded by some of the most distinguished Irish generals in the

history of Austria. In 1748 some of them were captured by the Algerians

and spent three years in captivity in Algiers. In 1777 the regiments were

involved in Brazil and in 1780 in the West Indies, Jamaica and the

Caribbean. They remained in Florida until 1791 and then they were sent

again to Oran to defend it against the Moors. They fought against the

famous Napoleonic soldier, Marshal Ney, and helped to defeat the French in

Galicia.

But the end of the Irish Brigade in Spain was in sight. The European

conscience was being pricked by the truth that on too many battlefields the

Irish faced their own countrymen. The Irish Legion, which was part of

Napoleon¹s army, opposed the Hibernian Regiment at the siege of Badajoz in

1811, and once again Irishmen faced each other on the battlefield.

Ireland Today

Ireland joined the EU in 1973, and hasn't looked back since. The

disciplines and the monetary contributions by Europe have made a huge

difference to the country. In 1632 the population of the island was 850,000

and was 8.2 million before the great famine of 1845 - 1849. Today the

population of the island is 5 million. In 2002 the total overseas tourists

to the Republic of Ireland was 5.9 million and was worth 4 billion to the

economy, and supported 141,000 jobs which represents 8% of the total

workforce of 1.765 million.

The Republic of Ireland maintains diplomatic relations with 154

countries. The

Department of Foreign Affairs has 66 Missions abroad - 49 Embassies, 5

Multilateral Missions and 12 Consulates General and other offices. There

are 108 Embassies from

foreign countries in the Republic. The Republic has 1094 foreign industries

which supports 133,246 jobs. Ireland hosted the 2003 Special Olympics,

with 7,000 athletes from 160 countries. The country has modern wind farms

for generating electricity, but you can still drink pints with old men in

Portumna.

Where to find information in Ireland, Spain and Belguim

Many people complain about the difficulty of obtaining information about the

Irish in Spain. The truth is that the archives of Spain contain an abundance

of information, whilst the information in Ireland is very scarce. Spain

began to systematically collect state papers from the 1540's onwards, whereas

in Ireland such information suffered almost complete destruction. Most

Spanish towns and cities have Municipal historical archives or Provinicial

archives. Central libraries, church and diocesan records are also a useful

source. All the important families also maintain complete records.

All the towns and cities on the northern half of Spain are important sources

of information, especially the coastal towns. Also the city of Simancas,

near Valladolid is a must. The cities of Malaga, Cadiz, Seville, Madrid,

Barcelona have huge amounts of information. The most important towns in the

northern half are La Coruna, Santiago, Bilbao, San Sebastian, Zaragoza,

Burgos, Valladolid, Salamanca. In the maritime Castilian province, the four

towns of San Vicente, Santander, Laredo and Castro Urdiales, have kept and

preserved the financial and legal records especially in Santander. All

records are preserved and catalogued to standard international levels : eg

Archivo General, Simancas (A.G.S), Estado, leg. 1751. Archivo Historico

Nacionall (A.H.N), Madrid, Calatrava, exp. 1834. Registered decreto of 18

September 1654,AHN H7892, f.304

In Ireland the only sources of information are the National Library in

Dublin, the Department of overseas archives of University College Dublin and

St Patricks College Maynooth. In Belgium, Brussels and Louvain are the

principal sources.

Epilogue

The story of the Irish in Spain is one of extraordinary generosity on the

part of Spain, and of devoted and loyal service on the part of the Irish,

some of whom are featured in this article, together with a brief account of

their lives. I hope that I have given a true and accurate account of the

Spanish Wild Geese and that the reader will pursue the story at leisure. I

work exclusively out of my own office attached to my house. The story of the

Wild Geese is huge and deserves a more auspicious location than my own

office. Portumna Castle has all the necessary heritage and space, and

perhaps our dream will come true some day.

Bibliography

The Irish Brigades in the Service of France, J.C. O'Callaghan.

The Wild Geese, M. Hennessy

The March of O'Sullivan Beare, L.J. Emerson.

The

Spanish Monarchy and

Irish Mercanaries, R.A.Stradling,

The O' Neills in Spain, Spanish Knights of Irish Origin, Destruction by Peace,

Micheline Kerney Walsh. The Irish Sword, Vol 4-11

The Wild Geese, Mark G. McLaughlin.

Wild Geese in Spanish Flanders,1582-1700, B.

Jennings.

Spain under the Habsburgs, John Lynch

The Flight of the Earls, John McCavitt

Relevent Websites

D. Ricardo Wall, Diego Téllez Alarcia.

http://www.tiemposmodernos.org/ricardowall

Ricardo Wall, ministro de Fernando VI y Carlos III

http://vial.jean.free.fr/new_npi/revues_npi/21_2001/npi_2101/21_spain_syw.htm, Diego Téllez AlarciaAlarcia.

For a translation, www.google.com, and search on "Ricardo Wall". The search results, Diplomatie, will offer a translation of half the above page.

Colegio Arzobispo Fonseca o de los Irlandeses (Salamanca)

MONUMENTOS:

Colegio de los Irlandeses. Salamanca

Colegio del Arzobispo Fonseca "Los Irlandeses"

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the following for their kind help and assistance, which

enabled me to complete this history. My own family without whom this

would not have been possible.

Tony McNamara, Teresa Tierney, Brian Murphy, Brid Murray, Louis Emerson,

Portumna and Galway Libraries, Ireland West Tourism, Industrial Development

Authority, Department of Foreign Affairs, Irish Embassy in Madrid, Spanish

Embassy in Dublin, Robert Hall in Frankfurt and the Librarians in La Coruna

and Salamanca. I am very indebted to Ann Harney of the USA, who

brilliantly manages my website, and whom I met a few years ago when she

crashed her car into Portumna Bridge. SR 15-11-03

© Copyright 1997 - 2004 Sean Ryan

Return to Homepage

As the leaders and rebels surrendered they were offered terms and their

lands were confiscated. Many requested transport to Spain where they

thought they could begin a new life. The ports of departure were mainly

Galway and Waterford. Galway served Connaught and Ulster and Waterford

served Munster and Leinster. They gathered up their papers, goods and

chattels, and were force marched to the ports of departure. They were

packed like cattle on the ships which were of inferior quality. Being

loaded as they were they contacted all kinds of diseases. Many died on the

journey and had the dubious distinction of burial at sea. The journey was

supposed to take 15 days but with unfavourable winds and enemy ships it

often took much longer. Private illegal ships were also a danger as they

attacked the official ships. Conditions on board these illegal ships were

very bad indeed and it was said that there was no problem in tracking them -

just follow the dead bodies floating in the water. All the ships landed at

the ports on the northern coast of Spain such as La Coruna, Santander,

Laredo, San Sebastian, Pasajes and Bilbao. The one exception was Cadiz on

the southern coast.

As the leaders and rebels surrendered they were offered terms and their

lands were confiscated. Many requested transport to Spain where they

thought they could begin a new life. The ports of departure were mainly

Galway and Waterford. Galway served Connaught and Ulster and Waterford

served Munster and Leinster. They gathered up their papers, goods and

chattels, and were force marched to the ports of departure. They were

packed like cattle on the ships which were of inferior quality. Being

loaded as they were they contacted all kinds of diseases. Many died on the

journey and had the dubious distinction of burial at sea. The journey was

supposed to take 15 days but with unfavourable winds and enemy ships it

often took much longer. Private illegal ships were also a danger as they

attacked the official ships. Conditions on board these illegal ships were

very bad indeed and it was said that there was no problem in tracking them -

just follow the dead bodies floating in the water. All the ships landed at

the ports on the northern coast of Spain such as La Coruna, Santander,

Laredo, San Sebastian, Pasajes and Bilbao. The one exception was Cadiz on

the southern coast.